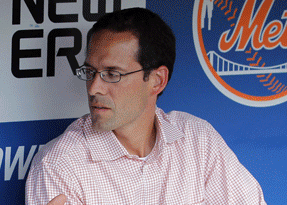

I want to thank Liz Peterson from Nautilus, who was kind enough to allow us to share an interview one of her writers, Kevin Berger, conducted with the Mets Vice President of Player Development Paul DePodesta.

In the interview, DePodesta discusses his early years with the Cleveland Indians and Oakland A’s as well as the book Moneyball. He dispels some of the myths regarding those Moneyball years and talks in depth about statistical analysis, how it has evolved, and the impact it has made in the way most organizations procure talent.

Nautilus was very kind in allowing us to post part of the interview here, but I encourage all of you to check out this exclusive content at Nautilus.

What’s the guiding principle of your work now?

The guiding principle of our work is figuring out a way to deal with uncertainty. That’s what we deal with every day—an uncertain future. What’s going to happen on the next pitch is uncertain. We can’t figure out exactly what’s going to happen, but if we can get our arms around a range of possibilities, that gives us a much better chance to at least make better decisions. We’re still going to be wrong a lot, but hopefully we’re wrong less often now than we were 10 years ago. But we’re never going to be in a situation where our analysis tells us what’s going to happen. These are human beings interacting with one another in a highly stressful situation. So we’re never going to be perfectly predictive. But that’s what makes baseball interesting, makes it emotional.

So is it better to have a man on first with nobody out, or a man on second with one out?

Sorry, but I have to leave that one open-ended for people. I’m sure they can find the answer somewhere online these days, but I’m not going to share.

When would a .300 hitter not be relevant?

To take it to an extreme, a .300 hitter who only hit singles and never walked once all year would be a below average offensive player. It’s not that batting average wasn’t important, it was that batting average was only a slice of the equation.

What do you mean by putting yourself in a position to get lucky?

Failure is a huge part of our industry. The best players fail every day. It’s no different than a championship poker player or a card-counter at the blackjack table. They lose all the time, too, but they put themselves in a position to get lucky by using pot odds or having an idea what’s remaining in the shoe. Over time, they win, even though there are a lot of losses along the way. We try to do the same. We know we’re still going to be wrong often, but we’re at least trying to give ourselves positive odds.

You’ve been with the Mets for almost three years. Given your statistical and scouting acumen, why do the Mets, if I can play the cynic for a minute, have a below-.500 average during that time?

It’s a fair question. I think a lot of it just has to do with time. And also just what’s available out there, and what flexibility you have to pursue what’s out there. But we feel that we’re getting closer to where we want to be. Four years ago, at the minor league level, from Low A up to Triple A, our clubs were under .500. As we sit here today, we have the best record in minor league baseball. Now, winning at the minor league level isn’t necessarily a goal, and it’s certainly not the definitive harbinger of success at the Major League level. And that’s ultimately what we’re there for: success at the Major League level. But I do think it’s an indication that progress is being made, that we have more productive players who hopefully, eventually will impact our Major League team.

Do you think fans see that on the field?

Probably not. Put it this way: It’s not the only way of doing things. There have been some very successful teams that do it differently. It still boils down to the competition on a daily basis, and that’s what the fans see on the field. There is a good measure of competitive balance in today’s game that was more difficult to come by in the late ‘90s. Team revenues are still far apart. And that still has an impact. But I do think some of this analysis has leveled the playing field.

Thanks again to Liz Peterson for reaching out to us and allowing us to share their interview with our readers.