The details of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the amazing work the Mets did in the relief effort, and Mike Piazza‘s dramatic home run in the first game back in New York have all been well-chronicled over the years. To read an outstanding recap of all of those events and their impact, please check out this piece by Metsmerized Online’s Marshall Field.

As is the case for many, the events of September 11, 2001 and the subsequent days and weeks are etched in my memory. My story begins in Manhattan the night before that fateful day, Monday, September 10. I recall watching the Giants game on Monday Night Football with friends. There was a dazzling electrical storm raging outside, prompting flippant conversations about Noah’s ark and biblical flooding. The Mets were off that night, and were playing better ball of late, yet languishing at 71-73, eight games behind the division-leading Atlanta Braves.

The next day began brilliantly. The sun was shining, and there was not a cloud in the sky. I had a meeting in Philadelphia, and after getting coffee for the road, exited the Lincoln Tunnel around 8:30. With sports radio annoying me (the Giants had lost and the Mets were almost done), I put in a CD for the trip, and drove down the New Jersey Turnpike oblivious to what was about to happen. If I had looked to my left, I would have seen the horror.

When I arrived at the hotel for the meeting, something was off. There was no staff at the desk. When I went to the meeting room, no one was there. I asked someone in the hall what was going on. I was informed, and directed to a large room where everyone was watching the events unfold on television. I have never been in a room where people were silent for so long.

New York City was not accessible for a few days, so my day trip ended up being a few nights in Philadelphia. When I did get back, the city was not the place I had left days earlier. It was eerie, scary, and violated. Nothing was normal, and it stayed that way for years.

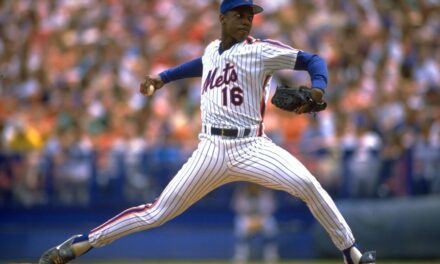

On September 17, 2001, something “normal” happened. The Mets played a game in Pittsburgh. They would play two more there (games that were originally scheduled for New York), and they won all three. Then, the Mets had the “Piazza” game on September 21. We all know what happened. Bigger than the games themselves, we had a small sense of normalcy. With everything else upside down, we had a slice of a safe haven, something familiar. Baseball gave us those feelings.

Throughout history, baseball has helped America heal, helped the nation feel normal when the world was anything but normal. When the United States entered World Was I in 1918, baseball decided to shut down the regular season on Labor Day. The World Series was moved to early September, and ended on, ironically, September 11 with the Red Sox being crowned champions. When the war ended in late 1918, as depicted in this article from Bleacher Report by Zachary D. Rymer, the “Inter-Allied” games were organized and then played in Paris in 2019. Baseball was one of the games played by former soldiers, as a way to help counties that had been at war develop new allegiances.

The U.S. took a very different, and perhaps landmark, approach during the World War II years. The 1941 season had been an interesting one, highlighted by Joe DiMaggio‘s 56-game hitting streak. With war now raging on two fronts, the 1942 season was in question. Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis asked President Roosevelt for his thoughts on whether, or how, to proceed. Roosevelt responded with what is known as the “Green Light Letter”. From Rymer’s article referenced above, here is an excerpt of Roosevelt’s letter to Landis.

“I honestly feel that it would be best for the country to keep baseball going. There will be fewer people unemployed and everybody will work longer hours and harder than ever before.

And that means that they ought to have a chance for recreation and for taking their minds off their work even more than before.

Baseball provides a recreation which does not last over two hours or two hours and a half, and which can be got for very little cost. And, incidentally, I hope that night games can be extended because it gives an opportunity to the day shift to see a game occasionally.”

Of course, the quality of the games wasn’t up to snuff, as many players were drafted into military service. Attendance was also down across the board (and fell each year during the war), but the American public still felt having the games go on was a good idea. From Rymer’s article, pollster George Gallup asked Americans their thoughts on baseball carrying on during wartime. Fifty-nine percent were in favor. Here is an example of the verbatim.

“Good morale builder…Good emotional release…Keep the ball flying…America wouldn’t be the same without baseball…We have to have recreation, and baseball is good clean sport…Good recreation for war workers…Good escape valve.”

The war years also saw the birth the All-American Girls’ Professional Baseball League (the subject of the Tom Hanks movie, A League of Their Own). The league drew over 175,000 fans in its debut year of 1943.

Baseball played through the Korean War and the Vietnam War. During those times, many memorable events happened, for example, Bobby Thompson‘s home run and the 1969 Mets.

That brings us back to September of 2001. When the gates opened at Shea on September 21, New York needed it. America needed it. It was uneasy, for sure, but important. Rymer quotes Mike Piazza from the catcher’s book, Long Shot.

“They came to say they weren’t afraid. The came to support and celebrate New York City. That’s what the Mets stood for, whether we wanted to or not, on the night of September 21. I don’t know that I’ve ever felt so determined, so compelled, so duty-bound to win a baseball game.”

There are other images from baseball post-9/11 that show its healing power. President Bush was on the field at Yankee Stadium to throw out the first pitch before a World Series game. That was powerful. It was tense. But it was yet another moment that the nation needed to show that we were not afraid.

In the years since 2001, there have been other instances of baseball helping us heal. We all remember David Ortiz and his impassioned speech on the field at Fenway Park following the Patriots’ Day bombing at the Boston Marathon. The games went on.

Baseball has passionate fans all over. We may yell (sometimes at each other), but this game brings us together. It’s part of our circadian rhythm. When we have it, things feel normal. The game can make us feel better, particularly during tumultuous times. President Roosevelt saw this in 1942, when he wanted the games to go on during the world’s biggest conflict in its history.

I can’t think of a more fitting way to close than to use the Terance Mann quote from Field of Dreams. It says a lot, and speaks to the incredible healing power for baseball.

“The one constant through all the years, Ray, has been baseball. America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It has been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt and erased again. But baseball has marked the time. This field, this game: it’s a part of our past, Ray. It reminds of us of all that once was good and it could be again.”