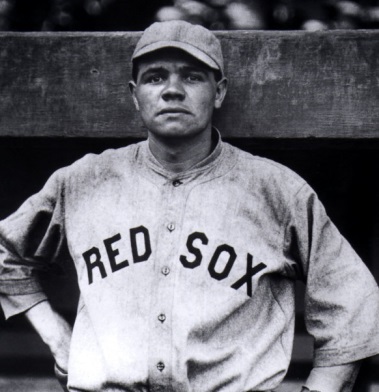

On January 3, 1920, Red Sox owner Harry Frazee sold Babe Ruth along with mortgage rights on Fenway Park to the New York Yankees. On January 4, 1920, there were no newspaper articles talking about ‘The Curse of the Bambino.’ For a curse to gain traction two things must happen. First, there must be the passage of time. Secondly, a reversal of fortune based around strange and unexplainable events from that point forward must occur.

On January 3, 1920, Red Sox owner Harry Frazee sold Babe Ruth along with mortgage rights on Fenway Park to the New York Yankees. On January 4, 1920, there were no newspaper articles talking about ‘The Curse of the Bambino.’ For a curse to gain traction two things must happen. First, there must be the passage of time. Secondly, a reversal of fortune based around strange and unexplainable events from that point forward must occur.

Prior to trading Ruth, the Boston club had won 5 of the first 15 World Series played. It would take 86 years to capture their 6th. And as New Englanders waited, they watched the Yankees win 27. The curse ended on October 27, 2004 when Boston completed a sweep of the Cardinals. The final out was recorded on a comebacker to the mound off the bat of Edgar Renteria. Renteria, like Babe Ruth, wore no 3.

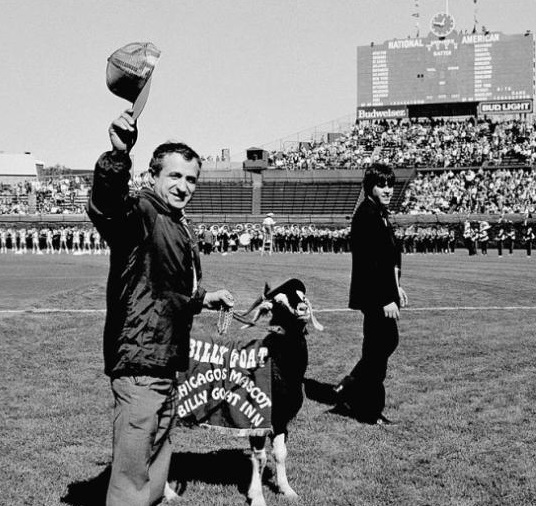

In 1945, the Chicago Cubs were facing the Detroit Tigers in the World Series. In the stands at Wrigley that afternoon was Billy Sianis, avid Cubs fans and owner of The Billy Goat Tavern. Sianis brought his pet goat to the game but when fans seated nearby complained about the goats’ odor, security had both of them physically removed from the stands. Furious, Sianis shouted, “Them Cubs, they aint gonna win no more.” Not only have the Cubs not won a World Series since then, they have never even returned to the Fall Classic.

Over the last few decades, we have shaken our heads more times than we can recall at the amount of absurdities and “unexplainable” bad luck that has befallen our Mets. But maybe, it’s not a simple case of bad luck. Perhaps, just perhaps, the Mets, like the Red Sox and Cubs, are cursed.

To look for the origin of this curse, one must go back. Way back. Before the Mets even existed.

The year was 1957 and Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley was insistent on moving his team 3000 miles away to Los Angeles. For Major League Baseball to approve a transcontinental move, a second team would also need to relocate to California. The westernmost team at the time was St. Louis and it would be too costly to have clubs fly another 1500 miles for just 3 games. Enter Horace Stoneham, owner of the New York Giants. Stoneham, like O’Malley, was getting nowhere in his quest for the city to build his club a new stadium. When the Giants decided to vacate the hills of Coogan’s Bluff for the hills of San Francisco, there were only three dissenting votes. The nays were that of Joan Whitney Payson, her husband and M. Donald Grant. When the relocation was officially announced, Joan Payson immediately sold her shares of stock and promised to do whatever necessary to bring National League Baseball back to New York.

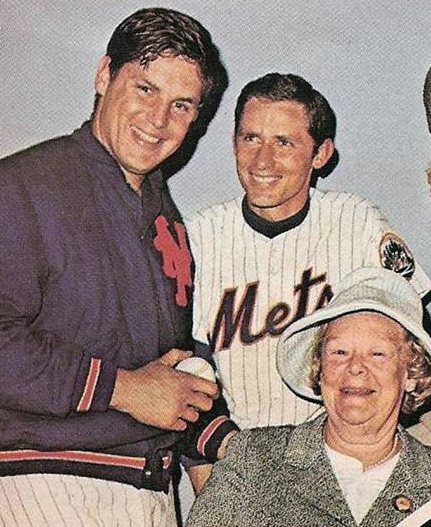

Her dream came to fruition in 1962 when the Metropolitans played their first game in, of all places, the Giants old stadium. Payson became the first woman in the history of North America to be a majority owner of a professional sports franchise. She was a brilliant businesswoman who was also an avid baseball fan. And although she loved her Mets—not as an investment but as a team—her heart was in San Francisco. Her favorite player on her beloved Giants was on his way to becoming the greatest all-around athlete the game had ever known. On May 11, 1972, at the unremitting demand of Payson, the Mets sent pitcher Charlie Williams along with $50,000 to bring The Say Hey Kid back to New York. Another dream of Joan Payson’s came true as she watched her cherished Willie Mays play for the team she owned.

At 41 years old, Willie was in the twilight of his career and was focusing on what to do after his playing days ended. The Giants were financially strapped and management could not keep Mays on payroll in any capacity, be it coach, hitting instructor, scout, etc…Payson assured Willie a spot on the coaching staff after retirement. He agreed and Willie Mays once again wore NY on his cap.

Payson made Mays a promise. His time as a Met would be brief and she could not justify having his number joining Casey Stengel’s 37 as the only numbers retired. She did, however, promise that no Mets player would ever again wear no. 24.

On October 16, 1973, Willie Mays played his last professional baseball game. On October 4, 1975, Joan Whitney Payson passed away. On August 7, 1990, the Mets “accidentally” reissued number 24. And so, ladies and gentlemen, begins The Curse of the Joanbino.

Kelvin Torve was a 30 year-old utility infielder when he entered the Shea clubhouse for the first time in the summer of 1990. He had played 12 games with the Twins 2 years earlier but now was awed as he looked around at his new teammates. Torve was back in ‘The Show,’ sharing a locker room with Doc Gooden, Darryl Strawberry, David Cone, Sid Fernandez and Frank Viola. He was handed a jersey, number 24, and suited up to take infield practice.

Fans began calling the front office. They started writing letters. That number was never supposed to be used again they reminded management. The Mets went on the road and while in the visiting clubhouse, equipment manager Charlie Samuels advised Torve of the uproar and asked if he’d mind changing numbers. Torve had no qualms about it. He was trying to stay in the majors and would do anything asked of him. On August 18th, he replaced his 24 with no. 39. The change of numbers happened on the road…as the Mets played, of all teams, the Giants. In the 10 days Torve wore Mays’ number, he batted .500.

In April 99, the number would be issued again, but this time not by accident. Newly acquired outfielder Rickey Henderson insisted on wearing 24. But it really didn’t matter by then. The Curse of the Joanbino had already taken hold.

As I alluded to earlier, for a ‘curse’ to have some legitimacy, there must be strange, unusual or downright weird events. Using the issuance of the Torve uniform as a benchmark, one can clearly delineate a reversal of fortunes of the Mets from that point forward.

Prior to 1990, our Mets were no strangers to bizarre plays. However, they always went in our favor.

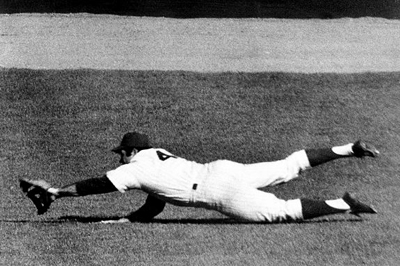

In 1969, the Mets shocked the baseball world by overcoming 100-1 odds and defeating the heavily favored Cubs for the division title. Facing the power heavy Braves in the LCS, the big question was could the Mets pitching quiet the lethal bats of Hank Aaron, Rico Carty, Felipe Alou and Orlando Cepeda. Our pitching failed miserably. However, the light hitting Mets beat the Braves at their own game, scoring 27 runs in a 3-game sweep. The Mets would go on to upset the Baltimore Orioles, a team that carried 4 future Hall of Famers–Brooks Robinson, Frank Robinson, Jim Palmer and manager Earl Weaver, along with 1969 Cy Young Winner, Mike Cuellar. Ron Swoboda, a well-known liability in the field, would make one of the most iconic defensive plays in Series history. A miracle indeed.

With the 1973 pennant hanging in the balance, another “strange” play occurred. On Sept 20, in a crucial game against the first place Pirates, Pittsburgh appeared ready to finally win in extra innings with a long blast to LF. The ball, however, did not go over the wall. Nor did it bounce off the wall. Rather, it bounced on TOP of the wall and back into play. Cleon Jones turned, fired to Garrett who pivoted and threw home to catcher Ron Hodges who nailed Richie Zisk at the plate. The Mets would win in the bottom of the next inning and pull to within half a game of first. Two weeks later the Mets were facing Cincinnati in the LCS. At the time my dad advised me, “The ghost of Gil Hodges was sitting on the fence and knocked the ball back into play.” I was almost 8 years old and that seemed plausible. Strange indeed.

And if the Miracle of 1969 and balls bouncing on top of walls weren’t enough, there’s also Game 6 in 86.

All of these peculiar plays went in the Mets favor. After Kelvin Torve was issued Mays’ number, the Mets underwent a reversal of fortune and everything from that day forward has seemingly gone against us. Although we only won 2 Championships and 3 pennants before the mishap of reissuing the number, the Mets still appeared almost charmed with good luck. After, we seemed, well, cursed.

Here are some of the bizarre incidents that transpired after Joan Payson’s promise was not maintained.

1991: The very first year after accidentally allowing another player to wear Mays’ number, the Mets draft 2 pitchers they intend to build their future around: Bill Pulsipsher and Jason Isringhausen.

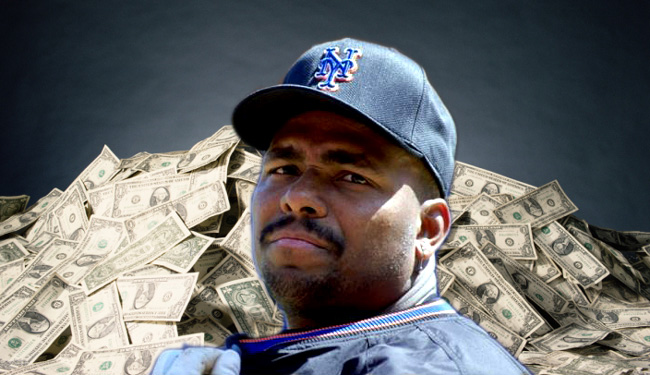

1992: The Mets sign Bobby Bonilla to a lucrative (at the time) 5 year/$29 million contract. Bonilla was a superstar in Pittsburgh. And although he was a native New Yorker just like John Franco, Lee Mazzilli and Ed Kranepool, he would become perhaps the most despised Met in team history. A subsequent renegotiation of his contract will see us paying Bonilla until he turns 72 years old. 72, the same year Willie Mays returned to New York.

Mid 90’s: The Mets spend big bucks to bring a pennant to Flushing. The plan falls short and instead they become known as ‘The Worst Team Money Can Buy.’

1999: After one of the most dramatic moments in team history, Robin Ventura’s famous Grand Slam single, the Mets lose the NLCS the following day on, of all things, a walk-off walk. It’s the only time in history a team lost the pennant in such fashion.

2000: The Mets lose the World Series in 5 games to the Yankees. Mike Piazza records the final out. Piazza didn’t ground out to the shortstop or strike out or pop up. He flew out—to center field, the same area Mays patrolled decades earlier.

2003: Earning more than $17 million, Mo Vaughn is the highest paid player on the team, netting more than even Piazza. His season ends on May 2 due to injuries. He retires from baseball.

2006: The Mets are expected to crush the Cardinals. St. Louis barely made the post-season and had numerous players injured. They were relying on a rookie to close named Adam Wainwright. The loss in the 7 game LCS was a shock and never expected. The decisive blow was a HR by Yadier Molina who hit only 6 HR’s all season. At the time, Molina was 24 years old.

2007: The Mets suffer what is regarded by many to be the greatest collapse in baseball history, blowing a 7 game lead with just 17 left. We even fail to make the wildcard.

2008: The Mets blow a 3 ½ game lead with 17 left. We again fail to even make the wildcard.

2009: Citi Field opens and in the inaugural game, a cat runs onto the field. Although it was not a black cat like happened to the Cubs in the heat of the 69 pennant, there is an interesting similarity. Fellow MMO blogger Ed Leyro pointed out at the time that in 69, the black cat ran out while Ron Santo was in the on deck circle. In 09, a cat ran out while David Wright stood in the on deck circle. Both Santo and Wright are considered the best third basemen in the history of their respective clubs.

2009: Mets players spend a total of 1,480 days on the disabled list. Our new home offers no immediate hope of a bright future. The Mets finish under .500 for the first time in 5 seasons.

2009: Luis Castillo against the Yankees. ‘Nuff said.

2011: After 50 years and 8020 games, a Mets pitcher finally throws a no-hitter. And from this point forward, for all intents and purposes, Johan Santana’s career comes to an end.

2013: Johan Santana’s salary is $25,500,000 for the season. He pitches zero innings.

2013: Fans finally see a light at the end of the tunnel. Matt Harvey conjures up images of Seaver and Gooden. He becomes the first Mets pitcher to start an All-Star Game in a quarter century. Six weeks later he is put on the disabled list. He is 24.

Maybe it’s just bad luck. Fate, perhaps? But one can easily see a difference in the Mets pre-Joanbino curse and post-Joanbino curse. In addition to the previously mentioned bad karma that has appeared since the no. 24 was reissued, there are also other, shall we say, “coincidences.”

2000 saw the Mets lose the Series to the Yankees. However, for the entire post-season, the Mets outscored their opponents, 60-51. 51…as in 1951, the year Willie Mays debuted. The last time the Mets won a World Series was 1986, our 25th year in existence. However, many don’t consider the strike-shortened 81 season a real season. Therefore, you can say that 86 was the Mets 24th season. Granted, that’s a stretch and somewhat tongue-in-cheek.

Here, however, are a couple more that garner some serious attention. Things that appear too coincidental to be mere happenstance.

Game 6 of 86 saw the Mets conclude the greatest come from behind victory in World Series history. We tied the series at 3 games and game 7 was slated for the following day. However, the hand of fate intervened and the game was rained out, played instead on Monday, October 27, 1986. 10-27-86. 1+0+2+7+8+6=24.

In 1969, the Mets swept Atlanta, then defeated Baltimore 4 games to 1. In 73, we defeated the heavily favored Big Red Machine in 5 before falling short to Oakland in 7. In 86, we defeated Houston in 6, Boston in 7. In 1988, we were upset in the NLCS by the Dodgers, 4 games to 3. All of these post-seasons appeared before Willie’s number was accidentally reissued. The total post-season victories—3 against Atlanta, 4 against Baltimore, 3 vs. Cincy, 3 vs Oakland, 4 vs Houston, 4 vs. Boston and 3 vs. LA totals out to…yes, you guessed it. 24.

In 1969, the Mets swept Atlanta, then defeated Baltimore 4 games to 1. In 73, we defeated the heavily favored Big Red Machine in 5 before falling short to Oakland in 7. In 86, we defeated Houston in 6, Boston in 7. In 1988, we were upset in the NLCS by the Dodgers, 4 games to 3. All of these post-seasons appeared before Willie’s number was accidentally reissued. The total post-season victories—3 against Atlanta, 4 against Baltimore, 3 vs. Cincy, 3 vs Oakland, 4 vs Houston, 4 vs. Boston and 3 vs. LA totals out to…yes, you guessed it. 24.

The bad thing about curses is they are inconsiderate when it comes to time. If the Mets are in fact cursed, how long will it last? The Curse of the Bambino lasted over eight and a half decades. The Billy Goat Curse is still ongoing.

On the positive side, Mays’ old number was recirculated in 1990. 24 years from that makes it 2014. On the other hand, Joan Payson was 72 years of age when she passed away. That would make it 2062 if 72 years has to pass. And worst of all, Mays hit 660 home runs.

Do I really think our Mets are cursed? Nahhh, of course not. Probably not. I’m sure it’s not real. I mean, come on. That’s silly. Right?

But just in case the spirit of Joan Payson is really, really upset and keeping in mind Willie’s 660 career home runs, here’s to the 2650 Mets.