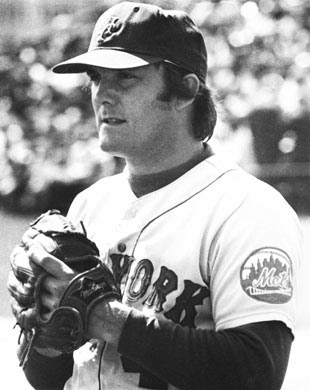

Someone once said “A baseball team is a living breathing thing.” If that’s true, Tom Seaver is our heart, Gil Hodges our brain, Gary Carter our lungs (he breathed life into the Mets in Game 6), Bob Murphy our voice, Keith Hernandez our eyes. And Tug McGraw? Tug would be our spirit.

America has changed dramatically since Tug last pitched for the Mets. In 1974, a new car cost $3,750, a gallon of gas .55 cents. The biggest hit that year was Barbra Streisand’s ‘The Way We Were,’ the top grossing film was ‘Blazing Saddles’ and the highest rated TV show was ‘All in The Family.’ The nation was reeling from a president resigning in disgrace and tiring of troops in Vietnam.

Yet, despite the passage of four plus decades, we still feel Tug’s presence.

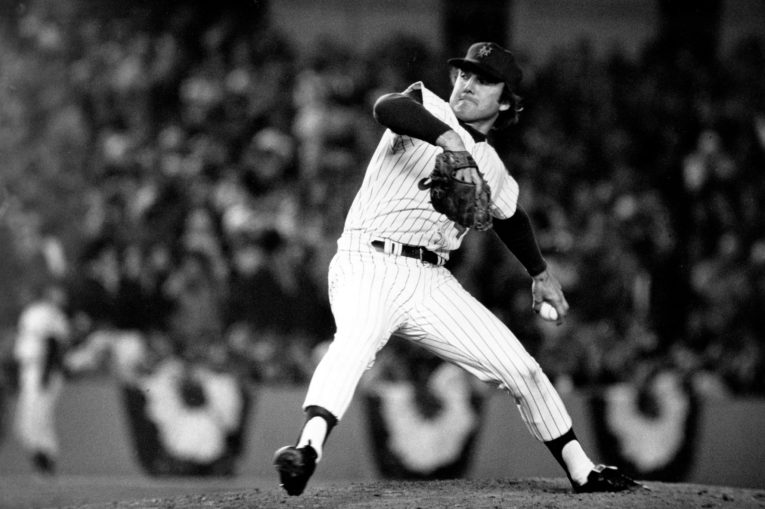

Those of us who were lucky enough to see Tug pitch are getting older. And perhaps, as it often does, memory embellishes things. But watching Tug perform his craft was a sight to behold, a privilege. It didn’t matter if the Pirates were down by a run with the bases loaded with Willie Stargell windmilling his bat. It didn’t matter if the Reds had the tying run in scoring position with no outs and due up was Pete Rose, Joe Morgan and Johnny Bench.

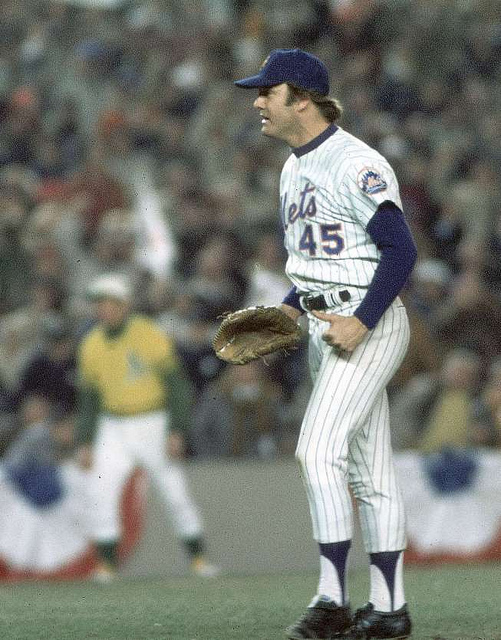

When you saw number 45 bounding out from the little bullpen cart and taking the mound, you knew—you just KNEW—everything would turn out okay. And three outs later, with Shea erupting in cheers, Jerry Grote walking to the mound shaking Tug’s hand and Tug shouting victoriously while slamming his glove against his leg, our thoughts were confirmed. Our fears alleviated. Tug made us feel better. Tug made us feel larger than life. Tug made us feel alive.

But his ascension to this level did not come overnight. It was a long arduous trek.

Frank Edwin McGraw was born in Martinez, CA on August 30, 1944. His mother nicknamed ‘Tug’ due to his “aggressive nature when he was breast-fed.” Immediately after graduating St. Vincent Ferrer High School in Vallejo, he was signed by the Mets on June 12, 1962. He was 17.

He spent one year in the minors, being used as both a starter and reliever and went 6-4 with a 1.64 ERA. The following year he made the Mets roster out of Spring Training, bypassing AA and AAA.

Tug was 0-1 with a 3.12 ERA in relief when on July 28 he made his first Major League start. The team was the Cubs, the location was Wrigley Field and the wind was blowing out. He lasted just 2/3 of an inning, giving up 3 ER before being hooked. The Mets lost 9-0.

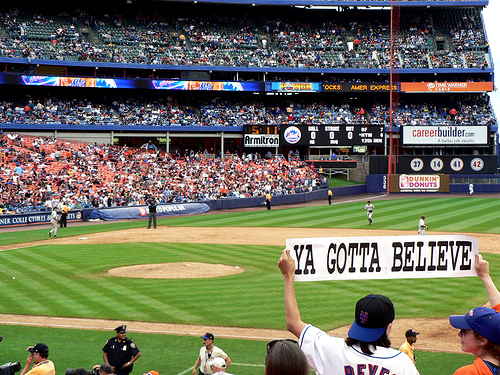

Ya Gotta Believe! ~ Tug McGraw

During that summer, the Mets were in Houston. America and Baseball was changing. For the first time ever the national pastime was played indoors in a stadium that resembled a UFO on the Texas prairie. Grass couldn’t grow inside so the game was played on a specially designed synthetic material called Astro-Turf. When a reporter asked Tug if he preferred grass or Astro-Turf, he replied, “I don’t know, I never smoked Astro-Turf.”

His second start was a complete game victory over the St. Louis Cardinals at Shea. It was his first win in the big leagues. His 3rd start had him facing Sandy Koufax. Tug defeated Koufax, 5-2. It was the first time the Mets ever defeated the Dodger legend.

Tug finished 1965, both starting and relieving, with a record of 2-7 and a 3.32 ERA. He tossed 97 2/3 innings, whiffing 57 but walking 48. Decent numbers for a rookie on a team that went 50-112 and finished 47 GB.

That September, with war in Southeast Asia escalating, Tug, a US Marine, reported to Parris Island. He became a rifleman, adept at firing the M14 and M60. He later reported to Camp Lejeune where he became, as he humorously said, “a trained killer.”

In 1966 he couldn’t regain his mediocre form. Still being used both as a spot-starter and in relief, Tug went 2-9 with a 5.52 ERA.

In 1967, he made 4 starts, going 0-3 with an embarrassing 7.79. Despite the Mets being an awful club and well on their way to another 100-loss season, even Tug couldn’t find a spot on the staff. He spent much of ’67 and all of 1968 in the minors. His career was on life support, his dream of being a big league pitcher hanging by a thread.

Early in 1969, Jerry Koosman got hurt. Manager Gil Hodges gave Tug a chance and put him in Kooz’s spot. This was Tug’s big opportunity. He could now prove to himself, a doubtful fan base and his manager that he deserved to be here.

Tug failed. He went 1-1 but his ERA was well over 5.00.

When Koosman returned from the DL, Tug was banished to the pen. He found his home.

Tug pitched exceptionally well, going 9-3, posted a career best to that point 2.24 ERA and fanned 92 batters in 100 IP.

However, he was erratic, streaky. And when the Amazins’ found themselves in the post-season for the first time ever, Hodges knew what was at stake. McGraw was too inconsistent to be trusted. He pitched just once, a game 2 slugfest, where he went 3 innings, allowing just 1 hit and 0 ER. He did not pitch again that October.

Tug would later say that 1969 was the turning point in his career. Although he had no impact on the post-season, he felt motivated by what the team did. “We were Goddamned Amazin!”

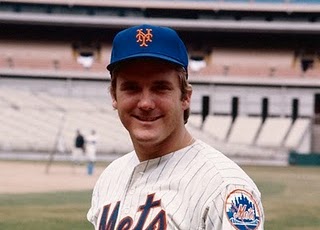

Quicker than a Nolan Ryan fastball and mastering his signature pitch, the Screwball, Tug became one of the premier closers in the league. He was respected by opponents, valued by teammates and adored by fans. He became arguably the most loved player ever to wear a Mets jersey. Tom Seaver was ‘The Franchise,’ the guy you’d enjoy sitting down and discussing Baseball with. But Tug was the guy you’d want to hang out with.

When he pitched in a game, Tug threw left-handed. However, when he loosened up in the bullpen prior to the game or played catch in the outfield with teammates, he threw right-handed. Fans frequently wondered who was that guy wearing Tug’s jersey.

The game was different back then. Closers didn’t come in to face just one batter. They earned the save. They stayed on the mound. No one cared about pitch counts. In 1970, Tug appeared in 57 games while tossing 90+ innings. He went 4-6 with a 3.28.

The following year, he went 11-4 with a 1.70 ERA, threw 111 innings in 51 games and recorded 109 K’s. Tug continued his dominance in 1972. He went 8-6, again posted a 1.70 ERA and set a team record of 27 saves, a mark that would stand until Jesse Orosco broke it in 1984. ’72 saw Tug picked for his first All-Star Game. In 2 innings of work he fanned 4 batters—Reggie Jackson, Norm Cash, Bobby Grich and Carlton Fisk—and picked up the win.

Tug McGraw had merited his spot amongst the greats of the day. And now, it was 1973.

Shockingly, once again, the Mets closer was erratic, unreliable and inconsistent. He found himself reduced to co-closer with Harry Parker.

On August 30, Tom Seaver suffered a heartbreaking 1-0 loss in 10 innings to STL. The Mets fell into last place and were 61-71. And although they were just 6 ½ GB, they’d need to leapfrog 5 other clubs.

M. Donald Grant held a closed door meeting with the players.

He endeavored to motivate the team that’d been playing run-of-the-mill ball most of the year. Not much heart. He said they needed to believe in themselves, believe in each other and believe in their abilities.

Of all people to echo Grant’s generic speech Tug seemed the least likely. After all, he was 1-6 with an ERA north of 5. If anyone should sit there and keep his mouth shut, it was McGraw.

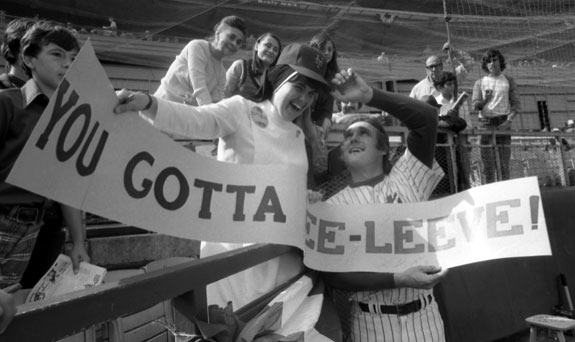

But not Tug. He began jumping around exuberantly, shouting and screaming, “Ya Gotta Believe! Ya Gotta Believe!” Some teammates chuckled, others rolled their eyes. Grant was offended and felt McGraw was mocking him. It was Tug being Tug.

Most likely no one really did believe. Perhaps Tug didn’t either.

The very next day, August 31, the Mets won a thriller over STL in extra innings and rose out of the cellar. Winning pitcher? Tug McGraw.

It was one of those strange pennant races that seemingly no one wanted to win. As the Phillies, Pirates, Cardinals, Cubs and Expos beat up on each other, the Mets beat up on everyone. Slowly but surely, the players started to believe. Fans started to believe. The Mets went 19-8 in September, Tug went 3-0 with a 0.57 ERA and recorded 10 saves in a month.

Number 45 took us on one hell of a ride.

Tug’s dominance continued into October. In the LCS he tossed 5 innings, scattering just 4 hits and allowing no runs. In the World Series against the A’s, he pitched in 5 of the 7 games, fanning 14 in 13 2/3 IP. It was Tug who picked up the win in crucial Game 2, a 12-inning affair that brought the Series back to NY deadlocked 1-1.

It was not to be. Despite falling short of another miracle, 1973 remains a true testament to the Mets will, drive and to believing.

The following year, the defending NL Champion Mets struggled all season. They hobbled across the finish line going 71-91. Tug also struggled, going 6-11 with a 4.16 ERA.

If you were a fan in the 70’s, you remember–vividly and painfully–the tortuously slow disassembling of the club piece by piece. Seaver, Koosman, Jon Matlack, Rusty Staub, Cleon Jones, Buddy Harrelson, Jerry Grote, John Milner. All sent away.

But it was number 45 who was the first to go.

On December 3, 1974, Tug, along with outfielders Don Hahn and Dave Schneck, were traded to division rival Philadelphia in exchange for Del Unser, John Stearns and Mac Scarce. However, the trade was nearly voided.

The Phillies accused the Mets of sending ‘damaged goods.’ New York had been tightlipped about McGraw’s shoulder problems during the ‘74 season. The Phillies quickly discovered the arm issue was a due to a simple cyst. The cyst was removed and the trade went through. The Mets believed that at 30 years-old McGraw’s career was probably over.

He’d pitch another ten years.

Stats show that Tug actually put up better numbers in Philly than NY. They, too, grew to love their new closer and for the last half of the decade, as the Phillies appeared in numerous post-seasons while the Mets floundered and flirted with 100-losses annually, Tug established himself as one of the best of his era.

In 1980, Tug saved 20 games and cemented the Phillies first Championship in history. Before a sold-out Veterans Stadium, he whiffed Willie Wilson for the final out of Game 6, did a quick dance on the mound like Rocky and was hugged by teammates like a conquering hero returning home.

Tug turned 40 in 1982 and although putting up respectable numbers, found himself in a set-up role for closers Ron Reed and Ed Farmer. It was time for Tug to step aside and let the national pastime move on without him.

Tug remained in Philadelphia as a sports reporter for WPVI through much of the 1980’s and ’90’s. In addition to sharing his knowledge with young prospects and penning several books during his career, he wrote a syndicated comic strip entitled “Scroogie.” Scroogie was a screwball pitcher who pitched for a team named The Pets. The Pets star pitcher was a refined guy named Royce Rawls (a clear-cut tribute to Tug’s former teammate Tom Seaver,) The Pets broadcaster, Herb, wore loud multi-colored sports jackets, a homage to Lindsey Nelson.

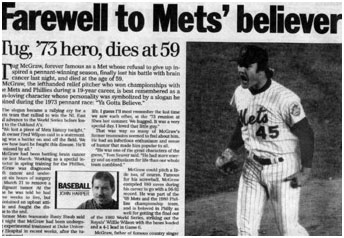

It was while working as a special instructor to the Phillies during Spring Training in 2003 when Tug realized something wasn’t right. He’d been getting headaches, forgetting names of players he worked with daily. Occasionally he’d arrive at the ballpark at the wrong time. Sometimes he showed up and the stadium was empty, having forgotten the Phillies were across the state playing elsewhere. A trip to a doctor, then an oncologist and a battery of tests revealed that Frank Edwin McGraw had a brain tumor.

He was operated on and the outcome was labeled a “success.” Chances of full recovery were “excellent” and Tug, we were told, should “live a long time.”

However, the tumor was not excised completely. It metastasized and returned to a part of the brain that was inoperable.

Tug McGraw was dying.

His final public appearance came on September 28, 2003. It was the last game ever played at Veteran’s Stadium and before a sold-out crowd, Tug stood on the mound and recreated fanning Willie Wilson for the final out of the 1980 World Series.

A little over three months later, January 5, 2004, Tug McGraw passed away. He was 59.

“Tug was one of the greatest characters in the game,” former teammate, friend and roommate Tom Seaver said. “But what people overlook was what kind of competitor he was on the mound. No one competed with more intensity than he did.”

Mike Schmidt said, “His passing is hard to take because his presence meant so much to people around him.”

Battery mate and close friend, Bob Boone, the first man to embrace Tug after that strikeout in 1980, stated, “He got more living out of his 59 years than anybody.”

Tug left behind 4 children and 2 step-sons. In 1966, he had, according to him, “a one night stand” with a woman named Betty D’Agostino. A son, Tim, arrived. But Tug didn’t accept the child as his own until Tim turned 17. Tug McGraw died in the Nashville home of his son. Both Tim and his wife, Faith Hill, were with him at the end.

Almost five years later, 2008, with Veterans Stadium gone, Tim McGraw walked to the pitching rubber at Citizens Bank Park prior to Game 3 of the World Series. He knelt down and spread some of his father’s ashes across the mound. Two days later, the Phillies won their second Championship.