Before 1965, any major league team could sign any amateur player. While there were “big money bonus” players (in the 1950‘s and 1960‘s, any player who signed for over $4,000 was considered a bonus player), many future greats signed for a few hundred dollars.

This system resulted in big discrepancies among major league organizations. Teams like the Yankees and Dodgers with large scouting networks had a dozen or more farm teams including two or three Triple-A teams while others had half as many or less.

In order to produce greater equality and to keep bonuses down and prevent bidding wars (the Angels in 1964 gave outfielder Rick Reichardt a then-record $200,000 for signing), baseball went to a draft system the following year in which all eligible amateur players were selected in reverse order of record from the previous year – a system that had been used effectively in pro football and the NBA for many years.

The system worked very well until the 21st century when agents such as Scott Boras established asking prices for their top amateur clients that caused teams that were both talent-poor and money-poor to bypass them in favor of more signable players. But, it’s hard to argue with the original premise of the draft when the teams that had the first selections in the first two drafts, namely the Kansas City/Oakland A’s and New York Mets became competitive and, in the A’s case, dominant in the years following the draft.

The A’s, in fact, could have been a true dynasty, if it wasn’t for owner Charles O. Finley deciding to cut back and rebel against high salaries and attempt to trade off practically every key member of his championship teams.

But this post is not about the Oakland A’s, but about the Mets, and this post is specifically about the 1965 draft. With the second pick in the draft, following the A’s choosing the consensus No. 1 selection in Arizona State outfielder Rick Monday (who became a good major league player, but not as good as a lot of players taken much later in the draft), the Mets chose pitcher Les Rohr, a high schooler out of Montana.

To say the Mets could have done better would be obvious – Johnny Bench was available, but everyone passed on him at least once and some teams twice – but most of the players drafted right after Rohr turned out to be no better. Ray Fosse (No. 7 pick by Cleveland) was probably the best of the first rounders, but the picks made directly after Rohr – Joe Coleman, Alex Barrett, Billy Conigliaro and Rick James (no, not the “Super Freak” Rick James) never really made it, either. Nor did Yankees’ pick Bill Burbach.

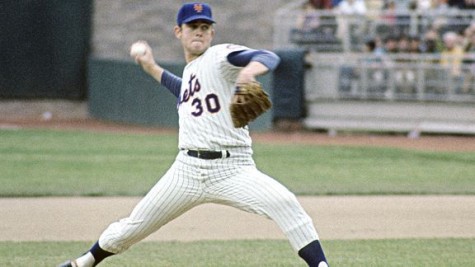

Rohr was a tall lefty with a big motion who the Mets fast-tracked through the minor leagues coming up for a look with the big club for parts of the 1967, 1968 and 1969 seasons, winning a total of two games. Rohr never had a really good season in the minor leagues, either. He had size and stuff, but lacked control and never really learned how to pitch. By 1969 of course, the Mets had a pretty solid rotation and there was no need to dwell on Rohr’s failure to make it. While Les proved to be disappointing, the Mets did make some nice choices in subsequent rounds.

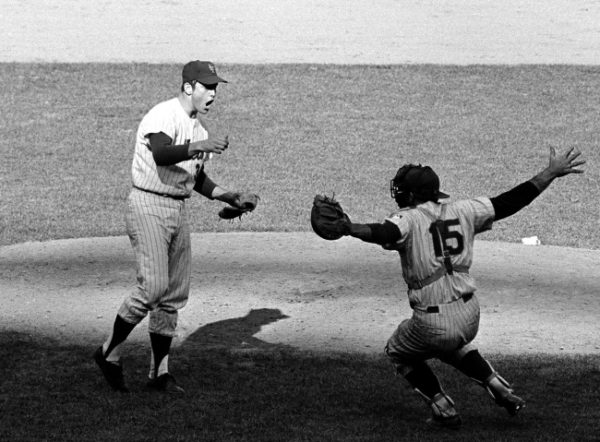

Looking back, it remains one of the best drafts in their history. Unfortunately, they didn’t get to reap the full benefits of their haul since they later traded away their best pick, Nolan Ryan, in what, of course, was one of the major trade blunders of all time.

The Mets’ second round pick, a catcher named Randolph Kohn, never signed with them. I believe he eventually played very briefly in the Dodgers’ organization without much success. That other catcher available in the draft, Johnny Bench got drafted several picks later in the same round.

Third-round pick Joe Moock was a fairly-well hyped infield prospect who made an appearance in the Mets’ broadcast booth right after he signed (Kiner pronounced his name to rhyme with spook, while Murphy pronounced it to rhyme with book). He actually played a few games for the Mets in 1967 despite limited minor league success above class-A Auburn. In 1968, he hit under .200 in the Double-A Texas League and never even made it to Triple-A.

Some of the notable picks included Ken Boswell in the fourth round, who became more or less the regular second baseman for several years. He was a good left-handed hitter, considered a better bat than glove, and had to be considered a good pick for the fourth round.

Jim McAndrew was chosen in the 11th round and became an effective fourth or fifth starter for the Mets, one of those guys who did much better in the big leagues than his projection. Another good pick.

Nolan Ryan in the 12th round was a gem, of course. Scout Red Murff loved this skinny righty out of Alvin, Texas and Ryan became an immediate strikeout sensation in the Mets’ system, averaging about two strikeouts an inning from Rookie Ball to Triple-A, before the Mets brought him up. Ryan’s future numbers could, of course, fill a book, or several books, as they already have, so I won’t go into them here. Suffice it to say, this was a great pick and subsequently a great loss.

Steve Renko in the 24th round was an important part of the Donn Clendenon trade and did quite well for himself as a starter with the Expos after going over there. Nice selection.

Don Shaw was the 35th round choice. He was a favorite of M. Donald Grant for reasons I’ve never figured out, but I do recall reading that Grant was opposed to trading him in several proposed deals. Shaw eventually went to the Expos in the 1969 Expansion Draft. He was a decent lefty specialist for a little while. Of course, any 35th round pick that even makes it to the big leagues has to be considered a plus.

Other picks who surfaced briefly in the major leaguers included Joe Campbell in the 44th round (0-for-3 with the Cubs in his major league career) and Barry Raziano in the 47th round (1-for-2 in a brief career in the American League).

So, overall, the Mets got one future Hall-of-Famer (Ryan), three Major League regulars (Boswell, McAndrew, and Renko), one player who enjoyed brief major league success (Shaw) and two who got a cup of coffee. A great haul? Maybe not, but certainly better than a lot of future Mets’ drafts. And any draft in which you select even one future Hall-of-Famer has to be considered positive.