On January 18, 1985 Tim Leary was quietly traded by the New York Mets to the Kansas City Royals. Leary was selected out of UCLA in the first-round (second overall) by the Mets in the June 1979 Draft. Less than two years later, at age 22, Leary made his major league debut. It lasted seven batters.

Life would have been better if no one said the phrase – ever — but it’s too late now. By the time Tim Leary first heard someone say it in his presence all he could do was go out and try to provide evidence to support the claims.

Leary, a UCLA graduate, overpowered hitters with a 96-mile per hour fastball, then buckled their knees with a biting curveball. In 1980, his first season of professional baseball in the New York Mets organization, he was unhittable. Leary was named Most Valuable Player of the Texas League. Honestly, that only made matters worse.

The occasional mention became an everyday occurrence. Scouts, fans, analysts were singing a chorus of praises that always ended in similar refrain: Leary was going to be “the next Tom Seaver.”

Mets manager Joe Torre and pitching coach Bob Gibson watched his 22-year old prospect blow away major league veterans in the Spring of 1981. Torre told the media Leary was “overpowering.” The Mets manager wasn’t alone in his praise. ”You look at him pitch and know that someday he’ll be a super baseball player,” added St. Louis Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog.

”I like that son of a gun on the Mets. What’s his name, Leary?” Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda told New York Times reporter Joe Durso. “He can throw the hell out of the ball.”

Torre and Gibson knew they’d have to convince GM Frank Cashen to get Leary on the 25-man roster. Cashen was staunchly conservative in his approach to promoting young, developing arms.

By the end of Spring, Leary made it difficult for Cashen to say no. The Mets GM gave in. Leary was in. He earned it. He pitched his way North. Leary would join a 1981 rookie class that included Cal Ripken Jr., Fernando Valenzuela, Tim Raines, Tony Pena and Mets Mookie Wilson and Hubie Brooks.

It was a typical cold, windy 46-degree Sunday at Wrigley Field in Chicago. It was a day filled with hope for the Mets. Hopeful that rookie Tim Leary would be all the things he was promoted to be, hopeful the 22-year old would not feel overwhelmed by the pressure, hopeful that they were witnessing the beginning of “the next Seaver.”

Leary struck out Ivan DeJesus swinging and Joe Strain looking at a called third strike. Two batters, two strikeouts and now hope was floating in the Windy City. Bill Buckner grounded out and Mets fans were confused. Was this Tim Leary or Tom Seaver?

In the second inning, after Steve Henderson lined out and Bull Durham struck out, Cubs third baseman Ken Reitz worked walked. Leary threw a wild pitch and Reitz moved to second. But Leary retired Scot Thompson on a fly ball to end the inning.

Did you see it? What … the wild pitch?

No. Leary felt “a searing pain” in his elbow as he worked to Reitz. Something was wrong, really wrong. “I felt some pain in my arm on the way north,” remembered Leary.

When the Cubs came to bat in the third inning it was Pete Falcone, not Leary pitching. Four days later he was placed on the disabled list. He wouldn’t throw a major league pitch for another 30 months. Cashen never forgave himself – or Torre – for what happened wrote Peter Golenbeck in Amazin’.

”Since I was 8 years old, I pitched hundreds of innings and was never hurt,” remembered Leary. “Now, I was hurt. Any time you even sit in a whirlpool, you get criticized. And I was taking whirlpools twice a day for months. When I went home to Los Angeles, I’d walk the beach. I became a loner.”

The whispers about being “another Seaver” faded – fast. Injury trumps all in professional sports. Being a “head case” is a close second and Leary was branded with both. Once a player is tagged, the climb to the majors becomes Mount Everest.

“The pressure is on in New York,” former teammate Terry Leach told Peter Golenbeck, author of Amazin’. “Some people can’t handle the attention, because they expect so much of you. Or you think they expect so much of you, so you try to do more than you’re capable of, and that’s not good. And that’s what happened to Tim Leary in New York. He was young, it’s hard to cope. You don’t know what it’s like until you play big league ball in New York. That is the big leagues.”

Leary reported to Spring Training in 1982, hopeful. He spent the winter exercising, strengthening his elbow. Leary pitched one inning against the Philadelphia Phillies and he was “roughed up.”

”Every time I threw, it hurt,” said Leary. “I couldn’t even pitch. I went back home, and didn’t do much of anything except walk the beach and worry. That was the low point.”

In June 1983 Leary visited Dr. Daniel Alkatis, a nerve specialist in New York. In minutes Alkatis diagnosed Leary with a pinched nerve. “I’d been lying around for eight months, he found it in five minutes,” he said. “I still had a long way to go, but my mind was finally free.”

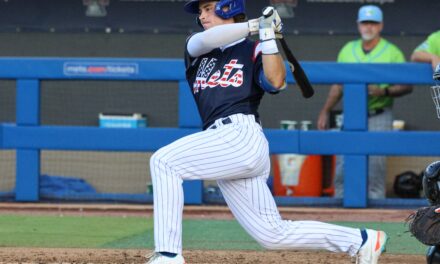

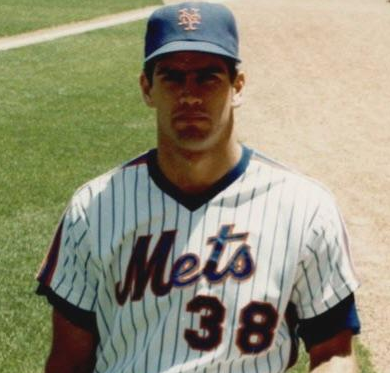

Sure the modest crowd that peppered the box seats on the final day of the 1983 season was a far cry from the dreams Leary once carried on his right shoulder, but No. 38 was pitching again. The “next Seaver” comparisons were gone, maybe for good, but he was back in uniform, on the mound, in the major leagues at Shea Stadium. And that was all that mattered now.

Leary pitched nine innings and beat the Montreal Expos. It was his first victory in the big leagues.

1984 was an ironic convergence of the past and then-present. Dwight Gooden, Tim Leary and Frank Cashen arrived in Florida for Spring Training.

Gooden was wearing Leary’s 1981 shoes, Leary was “damaged goods,” a reclamation project hoping for a spot on the roster and Cashen was waxing, bordering on hypocrisy, to the media about the lesson he learned.

”We’re starting to hear Gooden used as a standard of comparison for other young pitchers,” said the Mets GM. ”The scouts are starting to say that so-and- so has a Gooden-type fastball. That’s a form of subtle pressure in a way, but Gooden doesn’t understand what subtle pressure is, while Leary did.

”Gooden is very phlegmatic. He’s not burdened with a lot of hangups. I don’t want to say that Tim Leary was emotionally immature, but he was like Cassius in Shakespeare. You know, ‘Young Cassius has a lean and hungry look. He thinks too much.’ That can be dangerous.”