Throughout Baseball’s glorious history there have been hundreds of players idolized in their hometown. Occasionally, but seldom, does a player come along whose greatness extends beyond the city where they play.

And then there’s Roberto Clemente, the first ballplayer to be revered on two continents.

On the final day of the 1972 season, September 30th, Roberto Clemente doubled off Mets rookie Jon Matlack. It was the 3,000th hit of his illustrious career, a watershed mark only reached by ten others. People across North America and Latin America cheered. Three months later, Roberto Clemente died. People across North America and Latin America cried.

He was the first Latin player to win an MVP and the first Latin player to be enshrined in the Hall of Fame. He was also the first Latin player to win a World Series MVP.

He retired with a .317 career BA, 240 HR, and 3,000 hits. He was an MVP, a four-time batting champ, 15-time All-Star, and winner of 12 consecutive Gold Gloves from 1961-1972.

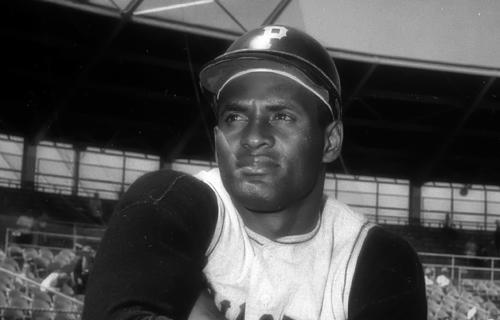

Roberto Clemente was born August 18, 1934 in Barrio San Anton, Puerto Rico, the youngest of seven. To help his struggling family, Roberto worked alongside his father loading and unloading trucks in sugar fields. But he always had his eye on the game he loved.

Upon turning 18, he was signed by Pedrin Zorilla for the Puerto Rican Professional Baseball League. He played some games at SS but mostly rode the pine. The following year, playing full time and batting leadoff for the Santurce Crabbers, Clemente batted .288. He was offered a contract by the Brooklyn Dodgers. Clemente followed in the footsteps of another trailblazer, Jackie Robinson, and played for the Triple-A Montreal Royals. Due to language difficulties, prejudice and ethnic clashes, Clemente struggled mightily and hit a disappointing .257. He was picked up by Pittsburgh in the rookie draft in November of 1954. Five weeks later, his older brother, Luis, died tragically on New Year’s Eve.

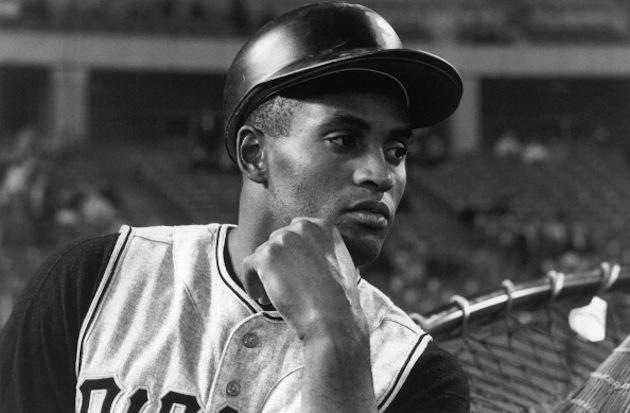

Roberto made his Pirates debut on April 17, 1955 and encountered much of the same prejudices he faced in Montreal. He was a Latino who spoke little English. He was of mixed-African descent. Just eight years removed from Jackie Robinson, Americans were still adjusting to breaking the color barrier. The Pirates were only the 5th team in the NL with a “minority” player. The young Clemente expressed frustration about racial tension, both coming from teammates and the Pittsburgh media. To lessen the impact of having a “foreigner” on their team, Pirates announcers called him Bobby Clemente.

Stress got to him throughout his career, manifesting itself in chronic insomnia. He once stated, “If I slept better I could hit .400.”

In his rookie season, Clemente managed a meager .255 betting average, but his defensive prowess caught everyone’s attention. Part of the reason for the lower than anticipated BA was that during that summer, Clemente was nearly killed when his car was plowed into by a drunk driver. He injured his back. It would plague him the rest of his career.

Pittsburgh sought out former Hall of Famer George Sisler to work with their young phenom. It paid off. The following year, 1956, Clemente batted .311. In a game against the Cubs, he became the only player in history to hit a walk-off grand slam inside-the-park home run.

1958 saw the Clemente-led Pirates finish over .500 and produce a winning season for the first time in a decade.

Each winter, Clemente returned home to play winter ball, reconnect with friends and to work with multiple charities. Except in ’58. That winter, he enlisted in the US Marine Corps Reserves and spent six months training at Parris Island.

In 1960, Clemente’s Bucs won the pennant for the first time in 33 years. They upset the heavily favored Yankees in a classic 7-game series. That season, Clemente batted .314 and was elected to the All-Star Game for the first time. There would be 14 more.

In 1964, Clemente led the NL in batting (.339) and hits (211) along with 40 doubles and scoring 95 runs. After the season he returned home with fellow countryman Orlando Cepeda where he was greeted by 18,000 adoring fans at the airport. The following month, as he and his bride Vera Zabala exchanged wedding vows, thousands cheered them outside the church.

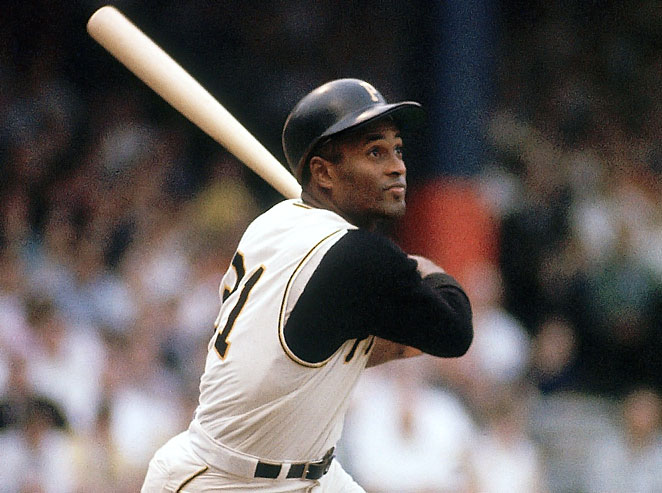

The 1960’s saw some of the games’ most dominant pitchers ever, especially in the NL. The decade was controlled by legends such as Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, Tom Seaver, Bob Gibson, Juan Marichal and Warren Spahn. But don’t tell that to Pittsburgh’s star right fielder. From 1960-1971 Clemente averaged .331 at the plate.

Clemente had it all. He played with the flair of Willie Mays, the swagger of Mickey Mantle and exuded the quiet confidence of Hank Aaron. His batting stance, the way he’d uncoil on a pitch like a cobra, was a sight to behold. The manner he rounded the bases with long loping strides, elbows and knees everywhere, was unforgettable. The way he’d wait in the on-deck circle on one knee and crane his neck hard to the right and left was mimicked by young kids on ball fields and backyards across America. He possessed one of the strongest and most accurate arms the game had ever seen. Vin Scully said of him, “He could catch a ball in New York and throw out a guy in Pennsylvania.”

On July 24, 1970, the Pirates played their final game at Forbes Field, their home since 1909, and moved into Three Rivers Stadium. Management also decided to honor their greatest star since Honus Wagner with “Roberto Clemente Night.” It was an emotional evening for number 21. “I spent half my life here,” he said. He received a scroll of over 300,000 signatures from his native Puerto Rico. Clemente used the opportunity to put forth a plea for businesses to donate to local charities. They did.

In 1971, the Pirates won 97 games and captured the NL East crown. They defeated the Giants in four games in the LCS and faced the defending World Champion Orioles, winners of 100 games and fresh off a 3-game sweep of the up-and-coming young Oakland A’s. Before game one of the Fall Classic, the confident Clemente stated to a reporter, “Nobody does anything better than me in Baseball.” After losing the first two, Pittsburgh won 4 of the next 5 and captured the Championship. Clemente batted .414 in the series, made numerous stellar defensive plays, and hit a decisive home run in Game 7 that gave Pittsburgh the 2-1 win.

Age, however, was beginning to take its toll. In 1970, he amassed just 412 AB. In 1972, at age 37, he missed 54 games with nagging injuries, but in what would be his final season, Clemente still batted .312.

The man who once said, “I’m convinced God wanted me to be a ballplayer” would never again play baseball.

On December 23, 1972, less than 3 months after recording his 3000th hit, a massive earthquake rocked Managua, Nicaragua. Aid was not reaching the victims as supplies were being stolen by the corrupt Somoza government. People were dying. People were hungry. People were scared. And the man who tirelessly worked with charities his entire life refused to sit back and watch.

Roberto Clemente believed his presence and reputation would put an end to the pilfering of Nicaragua’s leaders. He chartered a flight from Puerto Rico to personally deliver aid. On December 31, 1972, the Pirates’ legend helped load a plane, just as he had helped his father load trucks decades earlier. He was assisted by an Expos pitcher named Tom Walker who happened to be playing winter ball. Walker wanted to assist Clemente with delivering aid but Clemente wouldn’t let him. Walker was single. Clemente told him to go out and have fun. It was New Years Eve after all.

The Douglas DC-7 had a history of mechanical problems and the flight crew was inexperienced. The plane was overloaded by more than two tons and shortly after lifting off, it fell to the ocean just off the coast of Isla Verde.

As fans in the US and across Latin America mourned the untimely tragic death of the greatest Hispanic player to ever play the game, Clemente’s teammates gathered for his funeral. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn said in his eulogy, “He gave the term ‘complete’ a new meaning. He made the word ‘superstar’ seem inadequate.” The following season, Major League Baseball began bestowing the Roberto Clemente Award to the major leaguer with outstanding skill who is also heavily involved in charitable work and active in the local community.

Noticeably absent from the funeral was Clemente’s longtime teammate and best friend on the Pirates, catcher Manny Sanguillen. Rather than attending the service, Sanguillen flew down to Puerto Rico and spent days searching underwater for his friend’s body. It was never found.

Roberto Clemente left behind a wife, three small children, millions of fans and an indelible mark on the game God wanted him to play.

He played 16 years at Forbes Field and two at Three Rivers. Now, outside PNC Park stands a statue of Clemente where old and new generations of fans can see and appreciate Roberto the man, Roberto the player, and Roberto the legend.

The Expos pitcher, Tom Walker, who Clemente talked out of joining him on that fateful night, would eventually marry and have a family. His son… Neil Walker.