Even though Ron Swoboda wasn’t the best player or one that possessed a ton of tools, his name is forever revered by Mets’ fans for his contributions in bringing the first championship to Queens in 1969, after seven-straight losing seasons since the club came into existence in 1962.

What Swoboda was to many was ‘the affable everyman,’ a grinder on the field with a competitive will and drive to succeed, despite any shortcomings. What Swoboda lacked in talent, he made up for with his strong work ethic coupled with a benevolent charm.

The players that continually strive to improve and adhere to a team-first mentality are generally beloved and well-received, with Swoboda fitting that description perfectly. When an average player comes up big in the clutch, fans seem to gravitate to them even more, recognizing the height of the moment and appreciating the effort exerted on that pivotal play.

And boy, does Swoboda know something about coming up big on the grandest of stages.

Swoboda, 74, was a key member of the ’69 World Champion Mets, a team that had a 27-game improvement in the win column from their 73 victories in 1968. Their surge late in the season saw them eclipse the mighty Chicago Cubs and won the East Division by eight games.

Swoboda’s six hits in the World Series led both the Mets and Baltimore Orioles, and batted .400 with a .904 on-base plus slugging (OPS). What ‘Rocky’ is most remembered for in that Series was one of the greatest catches in Fall Classic history.

The setup was such: The Mets were up 1-0 to the O’s heading into the top of the ninth with a 2-1 lead in the Series. Tom Seaver was back on the mound looking to get three more outs to secure the complete game shutout and place the Mets one win away from a championship that the fans had clamored for.

Seaver retired centerfielder Paul Blair with a fly out to Swoboda, before back-to-back singles from Frank Robinson and Boog Powell put runners on the corners with one out in the inning.

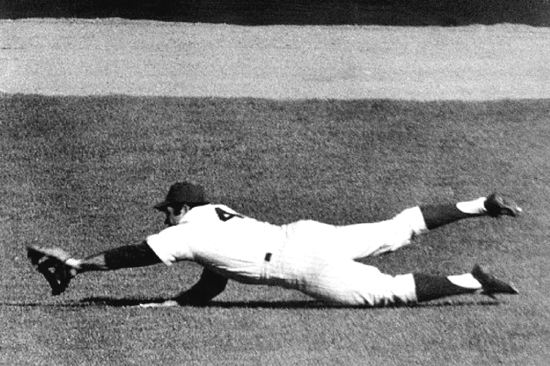

The next batter was Brooks Robinson, the eventual winner of 16-consecutive Gold Glove Awards at third, who went to the opposite field with a hard line drive that appeared to be trouble. Racing in and to his right, Swoboda – who was not known for his defense – laid out and caught the sinking liner on his backhand, propping to his feet quickly to make a strong throw home as Robinson tagged from third to tie the game.

Swoboda could’ve taken the conservative route and played the ball in front of him, however, he recalls reading the ball of the bat extremely well and getting a swift jump in his pursuit of the ball.

At that point, he was all in.

Seaver and the Mets got out of the inning allowing just the one run to score and won the game in the bottom of the tenth as Rod Gaspar scored from second after Orioles reliever Pete Richert was charged with a throwing error on pinch hitter J.C. Martin’s sacrifice bunt.

One day later, the Mets would take Game Five and be crowned the champions of baseball for the 1969 season, a memory that Swoboda will never forget.

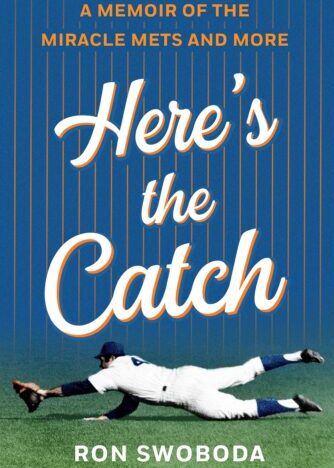

Swoboda recounts the storied ’69 season in his memoir titled Here’s the Catch: A Memoir of the Miracle Mets and More from St. Martin’s Press released on June 11. In the book, Swoboda shares interesting anecdotes and memories from his baseball career, which started with the orange and blue.

Signed by the Mets for $35,000 in 1963, Swoboda made his major league debut with the club in 1965. In his rookie season, Swoboda hit 19 home runs – a Mets rookie record until Darryl Strawberry broke it in 1983 with 26 – drove in 50 runs and posted a 103 OPS+. His 19 homers were third-most among all rookies that season.

In total, Swoboda played nine seasons with the Mets, Expos and Yankees before transitioning into broadcasting, where he’s currently calling games for the Miami Marlins’ Triple-A affiliate, the New Orleans Baby Cakes. And while he currently resides in New Orleans, the fondness and affection he holds for New York come through in the animated cadence in his voice when he recounts the years of memories he made with the Mets.

Swoboda’s book is a fun read that offers detailed insight into what it was like to navigate through the game, through good times and bad. With terrific anecdotes about some of the Mets all-time greats including Casey Stengel, Gil Hodges, Tug McGraw and Tom Seaver, along with what it was like to go through laborious slumps, dealing with being lifted late in games for defensive replacements and coming through in the biggest moments, the book brings about great nostalgia for one of the most beloved teams in franchise history.

I had the privilege of speaking with Swoboda in mid-June, where we discussed his memoir, the Miracle Mets and the upcoming 50th-anniversary celebration at Citi Field at the end of this month.

MMO: Talk to me a bit about your new book Here’s the Catch. When did you decide you wanted to write a memoir and was the 50th anniversary of the ’69 Mets a main motivator behind writing it now?

Swoboda: I had been telling these stories to friends and folks at dinners, men’s clubs and whoever would listen. I loved relating all of the stuff that I had been fortunate enough to go through as a player and just trying to put together all these little stories and entertain people.

I had a lawyer friend who told me that I needed to write this stuff down. And honestly, I didn’t feel any great compelling feeling to do that. He said to me if I didn’t write this stuff down and put it together now for the 50th anniversary, no one will ever buy it. [Laughs.] And I went, ‘I get that, I understand that.’

A few years ago I started writing stuff. I had a big stack of stuff I started putting together and I didn’t know what to do with it. I had an agent and he called me and asked how the manuscript was coming. I said, ‘How does dead in the water sound to you? I have this big pile of stuff and I don’t know what a book looks like. I don’t know how to put it together. I need somebody to help me whittle this thing into a book form.’

He introduced me to a guy named Jamie Malanowski, who was a writer in his own right. He’s published a couple of things but he’s also a speechwriter for Andrew Cuomo in New York and he said, “Send me the stuff.”

He started editing and we got it down to what looked like a decent manuscript size. He knows what a book looks like and that’s what we handed to the agent who shopped it around, and St. Martin’s Press bought the idea.

You want it to have your voice in the way you speak and the way you tell stories. Obviously, when you’re writing, there’s a little more detail than you can pluck off the top of your head, that’s why you write it. But you want it to have that voice, that sense of excitement and humor.

I wanted people to know how I felt going through slumps, sitting on the bench and going from that to the heights. Getting a little something going and now all of a sudden you’re in this thing and you’re producing something offensively and trying to make yourself a better outfielder at the same time.

I wanted people to feel the feelings I had when this was all happening. I hope that’s all in there because I was going for that.

MMO: What I also loved about your book is that you wrote about the environment and culture around the country at the time. You brought readers back to that era.

Swoboda: I couldn’t stress to people who’d aren’t old enough to have lived through that period of time – 1968-1969 – the culture, the war in Vietnam, Woodstock and all these great music festivals. The war and anti-war, identity politics, Stonewall Inn riots, women’s liberation movement and gay awareness.

And here comes the New York Mets! One of the least predictable things and we were center stage there. It was an incredible time when everything seemed possible.

MMO: Where did your passion for baseball come from and what’s your earliest memory of the game?

Swoboda: I was a kid growing up in Sparrows Point, Maryland, hard by Bethlehem Steel. Bethlehem Steel was the first integrated tidewater steel plant in America, meaning it was the first time they brought iron ore in by ship from outside the continental U.S.

The iron ore came from Cuba after the Spanish-American War and it sailed up not far from where I grew up. It sailed up and docked and they smelted the iron down and made from the irons steel and all kinds of steel products. Bethlehem Steel employed 35,000 people at its peak when I was growing up in high school, around the clock.

Around that steel mill were all these value-added companies that made other products from their steel. It was an incredible economy and dominated our world as we were growing up. But I was a kid that never felt any destiny, I just loved baseball and practicing the game. I played all kinds of things that I could do by myself.

I’d come to New York as a kid and saw these guys playing stoop ball and I had a set of steps in my house that I played step ball on. I threw the ball against the steps and I played that for hours.

I’m out in the street playing these games and I lived on a gravel road and there was an open field that I used to saw one of my mother’s brooms and she wondered, What the hell happened to the broom?

I’m down there hitting rocks, hitting gravel rocks into the woods and imitating the batting stances of the Baltimore Orioles, who were our team. And spending this time alone and doing this practice because I don’t’ know why I loved it. I loved the zen of it.

I’d get lost in these little one-man games I would play and then I eventually played on teams. You’re practicing with guys and I had a great friend of mine who I grew up with, Larry Butts, and he and I would practice together. I always liked the practice. I loved the zen of it and getting lost in the movements. I think without that I didn’t bring any natural, extraordinary abilities to the game except for the fact that I liked to practice. I think because of that I was able to refine some things.

I played in a big amateur talent in Johnston, Pennsylvania. They had a really good tournament. I’m 18 going on 19 and two guys walk in my house, a part-time scout that I had played for earlier with the Mets and a full-time scout, and offer me $35,000 to sign with them. They sort of presented it in a give or take way. My mom and dad were making about $12,500 between them, barely getting to $13,000 with both of their salaries. And here’s a guy offering you $35K! I was going to sign and it was simple.

MMO: Were the Mets the only team to make you an offer?

Swoboda: The only team, the Orioles never did. I was planning on going back to the University of Maryland and being a physical education major, and then this thing happened.

The big selling point from the Mets was they’re an expansion team and they’re terrible. They’re terrible now but they’re going to get better, and the road to the big leagues will be shorter because of that.

I didn’t need anything more than that and the $35K. I never saw that kind of money! I paid off my mom and dad’s house, bought myself a car and I bought my brother a car. We shared in it because that’s what it meant to me, a chance to make the world a little better for my family who gave me the opportunity. How could you feel any other way?

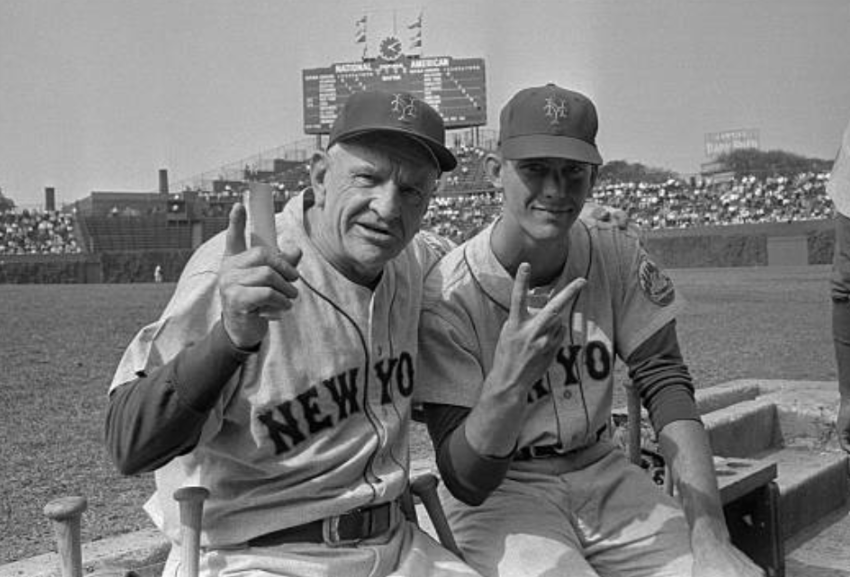

MMO: You detail a lot about Casey Stengel in the book. What was the Old Professor like to play under and what was your relationship like with him at a young age?

Swoboda: Amazing, amazing, amazing! Look, Stengel was a legend walking around, he was a treasure. The guy could sit down with the writers around him and reel off fifty years of baseball history. He may not get your name quite right, but he knew who you were and you knew what he was talking about.

I loved to eavesdrop on these sessions that Casey had with the writers and ‘Stengelese’ was this verbal journey he would take guys on. If he didn’t want to answer your question he would take you on the same journey down around the primrose path and by the time you came back, you might not remember what the question was.

There are two ways to censor: one is deprivation, you know, no comment. The other is inundation. He gave you so many words and stories that you may have forgotten your real question which he didn’t answer. But he did in some of these verbal journeys. There were little stories, like parables, nuggets of gold about how you play and examples of how players reacted in certain situations and what you needed to know as a major league player, and I listened to that stuff. I thought I extracted some good ideas and good stories out of it.

I thought he knew I was doing that and our relationship was excellent. He’d put me up there as a rookie in 1965 and he said, “You can’t learn how to hit these guys sitting on the bench,” in that gravelly voice.

It all started on Opening Day 1965. I’m on the bench in my uniform in Shea Stadium with 56,000 people there and the Dodgers and Don Drysdale on the mound.

Late in the game, we’re trailing – no kidding – and I hear Casey in that voice go, “Swoboda, get a bat.”

And you’re like, really? What are you going to say, no thank you, I’d rather not? No. You’re going to walk down there like you’re the king of the world and put your helmet on and walk up there and try not to pass out on the way.

Your heart is beating so fast that you’re dizzy and nervous as hell. You step in the batter’s box and you really wonder if people can physically see you shaking. You’re trying to act like a player and Drysdale throws you a fastball. BOOM, strike one. I’m like, I never saw it! I still haven’t seen it but it sounded like a strike. You tell yourself that you need to get some hacks up there and he throws you another one and you swing a couple of beats behind it and you’re 0-2.

I remember this thought occurred: The good news is that it doesn’t seem like this is going to take very long. [Laughs.] And then the next pitch is a slider and I could actually see it. I hit it on the line to the second baseman, Jimmy Lefebvre, and I’m out.

I’m going down the first base line and made that right turn towards the dugout but I was elated. I’m going, ‘Holy cow, I just hit a line drive off of Drysdale! You can have the out!’ The best out I ever made as a big leaguer, you know?

The next series I pinch-hit against Turk Farrell, and it was late in the game and I hit a home run. I hit that as far as any home run I ever hit. I just caught up with a fastball and banged it over the second wall in left field past the visiting bullpen. I mean, I bombed it and that was my first home run.

After the game, this shows you how naïve I was, they had a guy come up who said he had gotten the baseball and he wanted to know if I wanted it. I told him to keep it. I said, ‘Besides, I’m not sure that’s the baseball.’

The guy said, “What do you mean?”

I said, ‘If that’s the baseball, you couldn’t have gotten here that fast!’ [Laughs.]

Supposedly, Babe Ruth said that along the way and for some reason it came out of my mouth. We’re two Baltimore guys, you know what I mean? Two former Yankee right fielders, and there the comparison starts to break down.

MMO: Conversely, you write that your “failure to get along with Gil Hodges when I was playing for him sits like a stone in my gut.” Were there certain reasons that you believe were the cause of not being able to get along with Hodges?

Swoboda: I’ve had some time to think about it obviously, and I’ve always had a fractious relationship with authority. When it leans on me when I feel like it’s pushing on me, I don’t react well and Hodges was an authoritarian figure.

I had a pretty good year in 1967, my third year in the big leagues. I thought I sort of knew how to operate. But Gil had the way he wanted you to play as a player and the things he wanted you to do.

When I look back on it, the problems we had were all on me and my immaturity, and it caused a little friction between us. All Gil wanted you to do was act like a grownup and be the best player that you could be and help the Mets. I couldn’t always do those things. I could do some of them and not all of the time.

I would do things that would just annoy him and I wasn’t trying to annoy him, I was just immature. And because of that our relationship didn’t grow; it was rocky and it was on me. I’m responsible for that and it annoys me to this day that I couldn’t figure out how to make it better because he was a great manager and an incredible baseball mind.

One of the things I’ve taken putting 1969 back together [for this book] was you can go online and look at all the play-by-play sheets and box scores and you can look at the decisions Hodges made as a manager at various points in games and what he did. It was incredible. He had one of the most creative and adroit baseball minds that I’ve ever been around, and I played for Gene Mauch, reputed to be a genius and certainly a guy that knew a lot more about baseball than me. But I felt like Mauch was so brilliant that he could lose you in the complexity of his thoughts.

When Hodges did creative things, they all seemed to resolve themselves in an understandable way. And when you’re managing in the big leagues, the last thing you want to do is confuse your players and he never did. You might not agree with it and you might not want to get pinch-hit for but when you look back at the rationale for the things that he did, you go, wow, that was brilliant. And he did that all the time.

He should be in the Hall of Fame and that should be a no-brainer. The process that can’t make that happen to me is wrong.

MMO: You write how Hodges believed in platooning. which became clear early in spring training in 1969. You platooned with Art Shamsky, who you note was a better hitter for average. How difficult was it for you to play in a platoon and did that ever affect relationships with guys on the team?

Swoboda: Sham and I always had a good relationship. I thought he was a great player. He was a great hitter and he wasn’t writing the lineup card, so we knew what the deal was. It was a strict platoon with Shamsky and me in right, and that didn’t really happen until later on when I started to produce a little bit and made myself a little better outfielder.

We started platooning strictly in right field and you knew what the deal was down the stretch. Just like Donn Clendenon and Ed Kranepool at first base, Clendenon could’ve played against everybody, but Hodges believed that Eddie had something to offer against the right-handed pitchers and he strictly platooned. He did it at third base with Eddie Charles and Wayne Garrett and at second base with Al Weis and Ken Boswell, so we knew what the deal was at those positions.

It never entered the relationship with the guy. Sham and I hung out and we’re still good friends today. He’s one of the better organizers of the ’69 guys because he lives in New York, and when there are things to be done with appearances and such my phone rings. I appreciate that because he’s been a good friend over the years and will be until the end.

MMO: Heading into the ’69 season, did you have any idea that your club would be exponentially better like it turned out to be that year (73 wins in 1968 to 100 in ’69)?

Swoboda: Exponentially? No. I thought we would be better. I remember Gil Hodges told the writers in spring training that he thought we could win 85 games. I remember me and Kranepool looking at one another going, ‘Us? Is he talking about us?’

We had won 73 games the year before so 85 wins seemed like you were putting the carrot on a really long stick. But that was Gil. If we finished .500 that year, if we had won 81 games, to me, that would’ve been a pretty good improvement. And that’s where we were until about mid-June, bubbling around .500, and thinking that we’re a little bit better but no great shakes.

The next thing you know we’re in the middle of June and we just reeled off an eleven-game winning streak that started against the California teams at Shea Stadium and continued to the Coast and we vaulted into relevance. We’re looking at one another and there were five or so one-run games that we won in that streak and I think management, Hodges and Johnny Murphy the GM thought, we have to rethink this thing.

They had a chance to make a deal for Joe Torre with the Braves in spring training. The Braves wanted to get into our young pitching into maybe a Nolan Ryan or Gary Gentry and guys like that. Guys that they thought might be on the roster and Murphy said no thank you to the deal. The Braves traded Joe Torre straight up to the Cardinals for Orlando Cepeda, they didn’t get the pitching that they were looking for.

They [Mets] started talking to Montreal because Donn Clendenon was available. Mauch wanted to trade Clendenon to the Astros for Rusty Staub – which he eventually does – but Clendenon is not going to Houston because Harry “The Hat” Walker was there and the African American players thought Harry was a racist.

Clendenon had an option, he had an offseason job with Scripto Inc. He said, “You try to trade me and I’ll just leave baseball.”

So they had to deal with him. They told him to get in shape, play for Montreal and we’ll find a deal.

The deal was the New York Mets and they asked him if he’d go there and he said you bet your life! It was a 5-for-1 deal and Clendenon came our way and we had something we didn’t have because he had some serious power and a guy that platoons with Krane at first.

I think as we rolled out of June we’re a better team. Our pitching started to come around and Clendenon started showing what he could do for you and the rest starts to become history. We got better and reeled off some pretty good winning streaks. The Cardinals fell by the wayside, the Pirates fell by the wayside and it was us and the Cubs. I remember thinking at some point, Here we are playing better and better than I thought we could play, and we can’t catch the Cubs. I’m thinking, We arrived at something that we had never experienced before and we’re going to end up as the pumpkin in somebody else’s Cinderella story.

The Cubs looked like they were uncatchable.

Well, the last week in August and the first week in September is when the Cubs broke and collapsed. Was it because they were more mature and Leo Durocher – who didn’t invent baseball but certainly thought he did – played the same guys? They had Ernie Banks and Billy Williams; Hall of Famers and All-Stars. They had man-for-man maybe better players but they played the same guys and I think they hit the wall at the end of August and when they faltered we blew by them and never looked back.

I think we were coming out of the weeds and people still didn’t know if they should take us seriously or not so we had that factor. People didn’t know what to make of us, they didn’t have a handle on us until we started rolling. We didn’t have the responsibility; we weren’t carrying the baggage of expectations. We were just playing, just surfing on these amazing times. We were up on top of the wave and just rolling.

It was the easiest baseball I ever remember playing.

MMO: You write about the work you put in with Eddie Yost in ’69 where he hit you thousands of fly balls, grounders and line drives with the fungo bat. How crucial was that extra work in helping to refine your defense in the outfield?

Swoboda: A lot of people don’t understand that Shea Stadium was a hard outfield to play because the stadium stood so tall. Most fly balls and balls in the air never came out of the stadium, out of the backdrop of the fans. We always had pretty full stadiums and the fans are moving around. It’s like a fluid background and it changes with the atmospheric and it’s a tougher read and background. It’s tough to play there and a lot of people in their first exposure to Shea Stadium, outfielders especially, made mistakes on reads and I made my share.

With Eddie Yost, we came up with this routine. He’d get about 150 feet away with his fungo bat and he’d hit me line drives and groundballs; left, right, over my head and in front of me. I’m working on my hands and working on my footwork, but the thing you were really working on without even thinking about it was reading the ball off the bat. That read off the bat was so tough off that bad background in Shea Stadium. I started reading the ball better off the bat and if you did it good there you did it better everywhere else.

I became a better outfielder at a certain point in time and platooning with Shamsky in right field, Hodges stopped putting in Rod Gaspar as a late-inning replacement. He had done so in Seaver’s almost perfect game against the Cubs. I was sitting on the bench when Jim Qualls got his base hit to break the thing up. He had put Gaspar into the field in the eighth inning and so it was something that I felt like I was better at and didn’t want him to do. In my mind, I thought I could do better and I accomplished that before the end of the year. I wish I had learned more about hitting.

MMO: Can you walk me through your brilliant catch in Game 4 of the 1969 World Series? What was going through your mind in that moment?

Swoboda: We’re up on the Orioles, the heavily favored Baltimore Orioles for all the right reasons. They’ve got one out in the top of the ninth and we have a one-run lead. Frank Robinson singles, Boog Powell singles behind him and it’s first and third and one out.

Brooks Robinson was up and I was in a little bit, not way in, a couple of steps. I always moved back on the ball pretty well and I was comfortable with that. You wanted to be in a better position if you had the chance to catch a fly ball and throw Robinson out at home plate. I didn’t move so close that I was exposing myself to something over my head.

Robinson hits a line drive off to my right and I’m going from the get-go. I make the best jump I could make and from the get-go, I’m taking an angle like I’m trying to catch the damn thing. And what am I thinking? Well, Joe Pignatano, one of the coaches and a good friend of Gil Hodges, once said to me and he wasn’t joking, “Don’t think, Swoboda. You only hurt the team.”

I wasn’t thinking anything but baseball and I took a line that I thought would get me there. And 99 percent of the way there I wasn’t sure I was going to catch it. I was trying to intersect it and at the last second I laid out thinking that was the next best thing I could do. On my backhand, that ball hit me up in the webbing where I knew it was going to stay. I’m on a full head of steam and sliding through the grass and doing the roll and came up and threw home and fortunately, I was pointed in the right direction when I came up.

Frank Robinson, a smart ballplayer, tagged up like he should’ve and scored just ahead of my throw. But we stopped what could’ve been a two-run triple, or at the very least it drives in the tying run and puts Powell on third base. It would’ve been second and third at the very least if that thing gets by me and tied with them having the chance to go ahead. With every chance also that if we don’t get to it Powell could score from first. I always thought that Boog was going to have to wait just like Robinson to see if I caught it or not. He’s not tagged up at first but he has to wait and stop to see what happens with me and the ball.

MMO: And I think an underrated aspect of that play was how quick you got to your feet and made a strong throw home.

Swoboda: It’s funny, with this full-bore momentum on my backhand it was kind of balletic and for someone not normally associated with ballet in the outfield. But I did, I kind of skidded and got my feet back under me, and as I said before fortunately I was pointed in the right direction because that was where I probably was going to throw it.

I threw it home and it was all in a flash and in your mind it plays back like those stop-action pictures that were taken and captured. The Daily News owns that full layout still shot. They had a big, mechanical stop-action camera that was invented after World War II to take pictures of rockets that they were trying to develop in stop-action pictures. That camera was a big, bulky thing. It’s now in the Smithsonian Institute but it was a connection of a motor drive and a big, long lens; the thing was huge! And that was the camera that caught the still shots.

MMO: It must be a great feeling to forever be remembered for such a crucial play in the World Series.

Swoboda: For an average player, and that’s really what I’m trying to say in this book, I’m just an average guy who like every guy who gets a chance to play in the major leagues tries to be the best you can be and about all I could manage was flat average. But there are great moments possible when you are reaching out.

I think I quoted Robert Browning in there, the poet, about a man’s reach should exceed his grasp. It’s true that you can, in striving, be a little bit better than you are under normal circumstances for a moment. The average takes over later on but you can be a little better than you think you are. Everyone who is trying to do hard things should keep that in mind.

MMO: I loved the way you ended your book, with grafs from a New York Times article called “I Am Swaboda.” The article essentially is about how you resonated with fans because you weren’t a star player but you still were able to come up big and draw such fan appeal.

Swoboda: Do you remember the movie Frequency? It’s a kid and he’s got a radio and there’s an atmospheric disturbance and it turns out he’s talking to his father (Dennis Quaid) on this two-way radio back in time. His father had been killed in a fire and he’s talking to his father and they have no idea that he’s talking back to 1969. And the father is talking about the New York Mets and he says something to the effect of I’ll always love Ron Swoboda.

My picture is up in the movie and I met the guy that wrote the screenplay. I asked him, ‘Why did you pick me? We had all kind of cool guys on that team.’

This guy was not even a Mets fan, he was a California guy and he said he went into the newspaper files for that season and read my quotes and how I reacted to things that were happening in the ebb and flow of the season and said I sounded like the everyman.

And I went, wow, because that was all I was ever shooting for. That’s all I was ever after was to sound like a human who happened to be playing this game and in my book I hoped I’ve accomplished how you felt when you were going through the ups and downs of the season and you didn’t feel like you were Willie Mays or someone great. You were just a guy trying to do what you could do and lucky to be amongst 24 other guys trying to do the same thing who lived the dream.

MMO: Obviously the recent news about Tom Seaver’s health was disheartening and emotional for so many. Can you talk about what it was like playing behind a Seaver pitched game and the kind of competitor he was?

Swoboda: You had Tom Seaver followed by Jerry Koosman at their best, you’re not going to have too many losing streaks, period. They’re going to interrupt that. Seaver as your ace, Koosman as your warrior and he ended up drawing the other team’s ace a lot of the time.

Seaver was number one for good reasons. When Tom showed up in the big leagues in 1967, he was Hall of Fame quality from the get-go, from day one. When they took him out of the box and put him on the mound he was the same guy with the same confidence and the same stuff. All he needed was the time to accumulate Hall of Fame statistics, which he would do.

He was the same guy from day one.

I was talking about dementia and that Tom is fighting his way through and Bud Harrelson is experiencing the opening phases of Alzheimer’s. And I said this to somebody, those memories are treasures to me, treasure. And the thought that something insidious can sneak in there and steal them from you and they’re gone, is a tragedy on the level that I have no words for. The joke on the other side of that is I don’t have any marbles to spare and it is a frightening thing to me that it can happen to all of us. It scares the hell out of me, more than dying.

My dad passed away in April at the age of 96, and he really had his marbles and really had clarity up until the very last. I’m hoping that I’ve inherited some of his genetics. He lived it all though. We had a 96th birthday party and he let us celebrate him. After that, he stopped taking all of his medications and he let nature take its course and he was gone in less than a month. I felt like he said that’s it, that’s enough. And he left with the dignity that he deserved.

MMO: At the end of this month, you along with many of your teammates will gather for a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the ’69 Championship at Citi Field. What are you most looking forward to?

Swoboda: It’s going to be a crazy, busy and wonderful time. I think some of the guys that we haven’t seen, I’ve gotten to see Art a lot, Eddie Kranepool and I have stayed in contact, but they’ll be more fellas that you don’t see and that will be the joy for us.

There was a wonderful quote from Fred Shero when he was the head coach of the Philadelphia Flyers, and I was always a big Islanders fan so I wasn’t a great fan of the Flyers. Going into Game 6 of one of the Stanley Cups, Shero wrote on the blackboard for his team, ‘Win today and we walk together forever.’

That quote to me is all over the experience I’ve had with the 1969 New York Mets.

We walk together forever.

MMO: Thank you very much for your time today, Ron. It was a pleasure to speak with you about your memories and contributions to the 1969 Championship team. Enjoy the 50th celebration and best of luck with the book.

Swoboda: Thanks, man. This is going to be a wonderful celebration. Take care.

Purchase Ron Swoboda’s book here.