Introduction by Stephen Hanks

When I heard Gary Carter had finally succumbed to brain cancer at the too-young age of 57, I had two immediate memories. They weren’t of being at Shea on Opening Day 1985, when Carter hit his walk-off, 10th inning home run in his first game as a Met, or of Carter starting the two-out rally that won Game 6 of the 1986 World Series. I remembered first seeing him on TV in 1975 during his rookie year with the Montreal Expos and being delighted at his refreshing hustle and obvious joy for the game. And I remembered the magazine I created and once edited and the Gary Carter cover story that never got published.

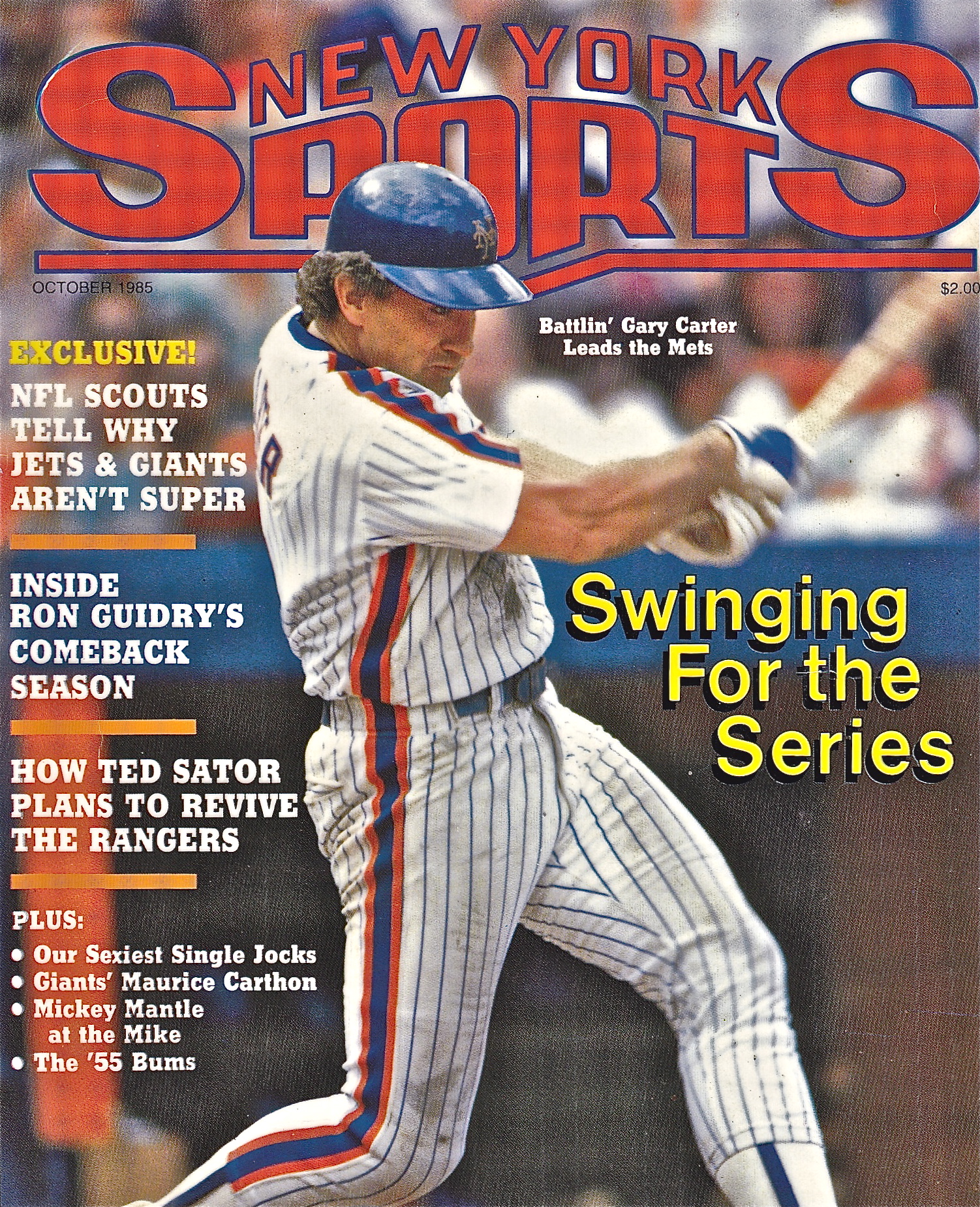

As I sat at Shea with my wife and then-business partner on that chilly 1985 Opening Day, I was proud that the New York sports magazine we had launched in April 1983 was starting it’s third year of publication (actually, we published just one issue in ’83, which had Tom Seaver on the cover). Although our bi-monthly magazine was still far from profitable, New York Sports was being critically-praised and items from our stories were being picked up regularly by the New York newspapers. We felt it was only a matter of time before the cash caught up to the kudos.

When in the summer of ’85 it appeared the Mets might have a shot at the post-season after 12 years in the also-ran desert, I made a leap of faith and decided that Gary Carter—the “last piece of the puzzle”—would be our cover story feature for the October issue. I assigned the story to Mark Ribowsky (whose most recent book is a biography of Howard Cosell), who had written the profile of Neil Allen for our ’83 launch issue, in which Allen blasted his teammates and the Mets front office and which contributed to his banishment to the St. Louis Cardinals for Keith Hernandez (no thanks necessary, Mets fans).

Right around the same time of that year, I received a call from an executive at the Charles Dolan-owned cable TV operation SportsChannel (which became Cablevision). The company was so impressed with New York Sports, they wanted to use one issue of the magazine as a promotion to all their subscribers—500,000 of them—and hype their fall hockey and basketball schedule. I almost dropped the phone. My wife the publisher immediately envisioned a subscription wrap around the cover with a letter from then-SportsChannel and Yankees announcer Mickey Mantle urging people to subscribe to the magazine. This was the absolutely ideal subscription list—all New York Sports fans—to put our magazine on the map, and the list and mailing to them would be free.

But the printing of 500,000 copies would not be and would cost around $15,000, not easy to raise when New York was still coming out of a recession, let alone bringing it in through advertising dollars. For two to three months, we scrambled to sell ads, borrow money, and pitch investors to get that one issue out and just couldn’t make it. So that September, with the October issue designed and ready for press, we reluctantly had to pull the plug and New York Sports was dead.

Thanks to the web, though, everything old can be new again. When I heard Carter had passed away, I went into my files and not only found that October 1985 cover, but also a copy of Mark Ribowsky’s insightful piece on “Kid” entitled “Gary Carter’s Agony and Ecstasy” that was never published and never read. I’m thrilled that 27 years later, MetsMerized Online can present it to its readers. Enjoy!

Gary Carter’s Agony and Ecstasy

New York Sports Magazine, Unpublished October 1985 Issue, Edited by Stephen Hanks

By Mark Ribowsky

Two months into his first season as a Met, New York celebrity Gary Carter is trying to impress me with his acquired knowledge of big-city life.

“Hey, I saw a great show!” he gushes, as he pulls on sweat socks at his locker. “My wife and me, we saw, uh . . . what’s that dance thing?”

I suggest names of some of the newer musicals, like Grind and Big River. Carter shakes his head. “No . . . uh, uh . . . gee whiz, I wish I could remember . . . You know, all the dancers telling their stories . . . Aw, geez!”

“Do you mean A Chorus Line?” I say, guessing the show that’s as old as Gary Carter’s career and almost as famous.

“Yeah! That’s it! Chorus Line. Wonderful show. Everyone should see it.”

Content that he’s done a New York kind of rap, Carter smiles and faces the challenge of another game for his Mets. He tucks a bat and glove under his arm and places his cap firmly on his head. With a distinct swagger, he starts walking toward the locker room door, but then stops abruptly. “I also saw the Christmas show at Radio City Music Hall,” he says proudly. Gary Carter was first in New York when he was nine. As a winner in the Ford punt, pass and kick contest, he won a trip for two to come here to do a commercial. He came from Fullerton, CA, with his mother. They spent time sightseeing—touring the Empire State Building and Radio City. Only three years later, his month died of leukemia. “Looking back, that time in New York was very special, just her and me,” he says.

Carter went on to lead the ultimate apple-pie success story: Star schoolboy coached and prodded by his father and his older brother Gordon, who played in the Giants farm system. Carter, a pitcher, was headed for UCLA to play baseball when his Sunny Hills High School coach made him a catcher to attract big league notice. Carter married the prom queen, was drafted in the third round by the Expos in ‘72, and while in the minors gained an early gung-ho reputation—and player dislike. He made it to the big club in three years, hit .270 with 17 homers, and made enemies by dislodging popular veteran Barry Foote from behind the plate. Four Expo Player-of-the-Year awards, three Gold Gloves, two All-Star game MVP trophies, and a decade of backbiting followed.

When the Mets traded for the catcher/slugger of their fantasies last December, they got everything they had never had plus a great deal more in Gary Edmund Carter. They did not get a Renaissance man—Carter would be the last to claim that title—but he is emerging as an endearing leader. At least he tries—tries hard.

That is Carter’s style in most matters of sport and life. Carter accrued a great deal of money and fame playing in Montreal because he tried hard—harder than some of his expatriated teammates could stand while suffocating in their uninspired ennui of playing in an unfriendly foreign outpost. Their distress was understandable: he made them look bad by comparison. Even one-year Expo Pete Rose complained last winter that Carter’s desire was wholly self-centered, his grinning, gee-whiz humility a front. Ignoring his own commercials hawking Grecian Formula hair dye, Crock Pots and Wheaties, Rose stirred up his moral outrage and said that Carter played for endorsements, and that his nickname—“Kid”—was all too appropriate for an immature self-seeker.

The Expos owner, Seagram’s chairman Charles Bronfman, had a sharper sword. After the ‘83 season—an off-year for Carter as the Expos again failed as a pennant contender—Bronfman said he regretted giving Carter a five-year, $1.8 million-per-year contract that year (fifth-highest in the game) to stay in Montreal. At the time, Carter had long been the major draw at the Expos’ gate, a gracious PR man for Canadian baseball, and widely regarded as the most imposing catcher in the universe.

Yet, Carter had to live in Montreal, among a kind of sly innuendo and misdirected flak that caused baseball people to scratch their heads in wonderment, given how well he played: .272 lifetime hitter, 215 home runs, those Gold Gloves, and smoke bounding from his nostrils while on the field. At 31, and in his salad years, Carter already had set a National League record for catching durability: six years leading the senior circuit in games caught. He is definitely Hall of Fame bound.

When Carter was ready for a needed change of scenery and suggested being traded to a team of his choosing, any general manager would have given one or several limbs to get him. The Mets were lucky. They had Gooden and Hernandez and Orosco, 90 wins in 1984, and plenty of young talent with which to trade. And they had New York. Gary Carter, after all, never said he didn’t want to make commercials.

“I haven’t felt anything like that [the Montreal problems] here. I feel like I’m very much appreciated. The fans are smarter and the players are great. It’s been a wonderful feeling.”

Gary Carter has reason to feel that golly-gee good saying this on a late May afternoon before a game at Shea with the Padres would be rained out. Though the Mets rest in first place, Carter, like almost every Met, isn’t hitting. He is mired in a 2-for-22 funk, carrying a .226 average—a lot worse since right fielder and slugger Darryl Strawberry, who bats behind him, went out for two months with a thumb injury. Yet Carter would seem to be technically innocent of harsh judgment. The Strawberry factor, for example, has been a telling if subtle equalizer: it is evident the league has been pitching around Carter’s hitting strengths without fear of George Foster (Oy George’s own average is a wheezing .207).

Then, too, Carter has been playing with a body that would be recalled if it were a Volkswagen. Coming into the season with a right knee healing from minor surgery last October (and which would flare up again in July), Carter immediately began taking hits from base runners that Joe Namath never got from blitzing linebackers. One collision broke a rib. Carter missed one game. Then, in Cincinnati, doing a stand-up slide to protect the rib, he sprained his left ankle. Carter spent seven hours in a cold-compress machine, wrapped the ankle, and was back the next game. “I don’t know how I played. Look at that,” he says, directing my gaze to an ankle that is roughly the size of a ripe casaba melon.

The effect on his bat is obvious: “I can’t plant my back foot. I don’t feel comfortable. You think you’re not strong, you over-compensate, do little things wrong.” Even so, it’s scary how profound Carter has been despite it all, his early-season noise still echoing around the tri-state area weeks later. Carter made his Opening Day anointment rite by crashing a 10th-inning home run against the Cards, and then proceeded to beat the Reds (homer), Braves (homer), Phillies (double) and Giants (single) with late-inning fireworks. From behind the plate, he threw out 14 of 32 base stealers, 10 of the last 16.

Most important, his influence on the pitching staff has been nothing less than megaton force. It’s no coincidence that Dwight Gooden is setting up and striking out more people with breaking pitches this year. (“If his breaking ball isn’t working early, I don’t let him throw all heat,” says Carter. “I get him to stay with the curve because it helps him get his rhythm, which makes all his pitches better.”) After Ron Darling shook off Carter and kept stubbornly throwing fastballs in one loss, he won on his curve his next start, while using his tailing fastball to blow away lefty hitters Carter knew would bail out on the pitch. After 12 years, Carter knows hitters like Betty Crocker knows angel food. The two big Met pitchers, whose egos are large, are like rapt pupils in his classroom. “I don’t plan to shake him off again until I’m 45,” says Darling.

“That’s what they wanted from me here, to develop this staff,” Carter acknowledges. “Normally, if a catcher can handle the pitchers, he’s doing well if he hits just .250.”

Carter makes his points in a thoughtful, honest, cliché-strewn way that is inoffensive because he does like to talk so much and because he is so earnest. Though his kinky brown hair has gaps and the wolfhound face is lined now, his big brown eyes are eternally childlike. They look straight into yours as he goes on: “Then, too, I want to be here so much that I’m puttin’ extra strain on myself. I’m still way up there, ‘cause I want to win so bad here, because these guys want it so bad. They’re hungry, whereas in Montreal we had the chance and flaunted it away. So it’s not like I can’t take a day off. I don’t want to. I will play my head off for that man. [A nod to manager Dave Johnson’s office.]

Photo: ESPN

The frustration, though, would continue for Carter. He began to hit a little in early June, raising the average to .241 with some typical late inning clutch hits, but fell off again. He went homerless for 27 games. The Mets, meanwhile, fell out of first place. In Montreal, it might have sparked a new round of anti-Carter sniping. This was not the case at Shea, however, not with so many lousy bats around. That’s all that Carter ever asked for in Montreal when things went bad for his team: equal treatment—good and bad—especially since, unlike other baseball millionaires, Carter works hard for the money.

Rusty Staub knows, having played with Carter for one season in Montreal. Says Staub: “Despite his problems there—and they weren’t of his making—he hardly has to prove his character here.” Staub says that the first thing Carter did after the trade was call the veteran Mets, a most unusual nod of deference since normal protocol is the other way around. “I don’t really know Gary; I don’t think anyone here does. But a bad guy?” Staub wrinkles his eyebrows in derision at the very thought.

With batting·practice washed out, Carter decides to hit in an indoor batting cage down the corridor. On his way to the hall, he peeks behind the door of a room in which Mets huddle around a videotape recorder. Believing that the tape on the machine is of last night’s game, Carter—a dead pull-hitter who hasn’t been waiting on the pitches the league has been keeping out of his wheelhouse—yells, “Pullin ‘ out too soon?” Hearing that, his teammates in the room snort laughter so loud that I can’t figure out what’s so funny—until I notice that the tape is of games of a more sensual nature and Carter’s question has been given a whole different meaning.

Carter flits down the corridor without even realizing the mistake. He bounces along, merrily humming and greeting Shea maintenance men, who are delirious that he notices them, “Gary, ya gonna run for mayah?” one guy asks.

I think I’ll let Mr. Koch handle that,” Carter says, smiling. In the hitting room, a slab of Astroturf surrounded by chicken wire, the fence rattles as cracks reverberate and baseballs fly. Carter takes his turn, eschewing his normal open, facethe-pitcher, yank-the-inside pitch into-the-next-county stance to fool with more closed stances he probably will never use. (A Met tells me later: “Gary says he wants to go with the pitch more, but he’s got a macho attitude about hitting. He’ll always revert, try to pull an outside pitch and pop up. This is no knock, he’s just that kind of hitter, and he’s been pretty damn successful.”) Carter’s swing is impatient, vicious and quick, his feet setting in place almost as he swings, as though he’s on roller skates. Each cut brings a loud grunt. Periodically, Carter’s eyes drift off and focus on a world totally inside his head. At those times, he seems briefly out of touch with the world, and the smile is inoperative. It is almost as if the energy of The Smile is a drain on him, and he must flee from it even for a few moments. But that is a Gary Carter we will never know. In those private meditations, Carter may think he does have to prove things—through sheer habit.

Four years ago, I interviewed Carter for a national magazine, and the whispers in the Montreal clubhouse were just turning into rumbling. But what I thought contributed to it was Carter’s own inability to handle it, to just say screw ‘em and forget about it. Instead, sensitive to spoken or implied criticism (Carter’s wife Sandy says he is far too sensitive for his own good), he defended himself so often and eagerly that I felt he had a kind of whiny, excuse-making tone. I sense that same tone today when he speaks of his injuries in relation to his average—especially when he says, as he does often, that he’s not making excuses.

Even so, it was exaggerated in Montreal because he tried so hard to be a regular guy that the mixture of goodness and ego was like oil and water. Worse, he and everyone else cohabited and competed for the same limited-dollar concession on strange turf. Says Carter: “It’s hard up there, the tensions build up over little things; the language, taxes, and customs checks. It’s a whole culture shock. The club puts you up in little crackerjack apartments, and everybody’s miserable.

“Well, I tried to make the best of it. We bought a home there, became landed immigrants, self-incorporated for tax advantages. I traveled around Canada in the winter promoting the team. When I was in Halifax and Trowshoe and Thunder Bay in 20-below cold, everyone else was home fishing.”

Yet Carter was perceived as selfish by players, and a litany of real or imagined grievances mounted. Carter played harder on national TV, he grinned mostly for the media and fans, his showboating angered opponents, and he really traveled Canada to promote himself. The Expos’ nickname for Carter was “Lights,” as in lights, camera, action.

Carter tried exceedingly hard to change perceptions. Last year with the Expos, he replaced the clubhouse stools with director’s chairs. But because he got them from one of his many Canadian commercial clients, it only added to the cynicism. “[Centerfielder] Andre Dawson said, ‘Carter got ‘em free so why should I say thank you?’ I mean, that is really petty.” It eats like acid at Carter’s gut that of all the Expos, Dawson and leftfielder Tim Raines have been his loudest critics since the trade. “And I thought those two were my best friends there. When Andre had knee trouble, I encouraged him, ate with him, and told him to hang in. And Timmy is my neighbor in West Palm Beach [his off-season Florida home].I drive his kid to school . . . It’s so crazy. “

Pressed for an explanation, Carter does not hesitate. “The only thing I can think of is jealousy,” he says simply without anger or hurt. “Maybe advertisers didn’t use Andre because he’s a monotone, I don’t know. [Pause] Andre was winning the batting title one year, and then died in September. Timmy had a drug problem. [Pause] I guess the easiest thing to do is divert attention from your own failures.”

It is Carter’s eyes that betray the anger and hurt his voice tries to hide when he describes how Bronfman called him in before the ‘84 season and began “asking crazy questions” about whether he could handle the “situation” in the clubhouse. Carter was pushed to the edge by more of the same when Bronfman, who knew he’d have to pay big bucks to Raines and other Expos, met again with his All-Star catcher after the season. Carter, who was proud to have rebounded from ‘83 to lead the league in RBIs, felt the owner was trying to goad him into asking for a trade. Not seeing any other way out, he obliged. Mets GM Frank Cashen coughed up starters in infielder Hubie Brooks and catcher Mike Fitzgerald, and a potential starter in centerfielder Herm Winningham, but Cashen’s Cheshire cat grin told you he felt he got Carter for minor barter.

When the trade was made, Carter got well-wishing calls from only three Expos. Although delighted with the move, there is a noteworthy crack in the happy facade when Carter says of the dark memories, “It hurt, there’s no question it hurt because I didn’t understand it. But one thing I learned from it is that you can count your friends—I mean, your true friends—on your hand.”

Carter obviously doesn’t see his mayo-on-white caricature as a barrier to outside fame and fortune. He freely admits that he has no interest in world issues, his most treasured possession is his baseball card collection, and he hasn’t read a book in years. He enlisted sports agent Matt Merola, a man familiar with the New York turf, to line up clients, and the first ones became Polaroid, Warner Lambert and American Chicle. Carter’s face also is on more Newsday posters along the No.7 Flushing subway line than a band of delinquents could cover with graffiti.

A month later, on July 3rd, I return to Shea in the midst of a dramatic reversal for Carter and the Mets. Carter, as expected, had begun to hit, and hard. He’d boosted his average to .269 by hitting .350 over the last 22 games, with five homers and two more game-winning hits. Carter now led the Mets in runs, hits, total bases and RBIs. Yet, in a weird irony, the Mets had responded to this production with a vicious tailspin—losing eight of nine and 19 of 28 games. Their bats now lying in state, they hadn’t scored an earned run in 30 innings and had one extra-base hit in 23 innings. Strawberry was back, but Mookie was gone for awhile with a shoulder injury. A win the night before over the putrid Pirates snapped the Mets’ six-game losing streak. Carter, who wouldn’t be caught grim in a Turkish prison, goes only as far as a what-can-I-do pursing of smiling lips to indicate his own bedevilment. “I started hitting because I got healthy,” he tells me, with obvious satisfaction. “But the team . . . it’s been frustrating for everybody. Everybody’s trying to do too much and putting additional pressure on themselves.”

Which is exactly the kind of cliché you’d expect Carter to utter about circumstances like these. And yet Carter, who will answer any question, will surprise you. Prodded deeper into the specifics of the Met slide, Carter rather candidly mentions why Hernandez has slid from the .280s to .251 (“He’s had his divorce settlement on his mind”). He also says he has misgivings about Dave Johnson’s strict platooning at non-power positions, second and third base, which he feels hasn’t allowed Ray Knight and Wally Backman to become stable regulars—though he adds, “I still back Davey up a hundred percent. “

As for his filling the role of motivator/leader during the bad spell, he says, “I’ve tried to keep a positive outlook. I like to think it’s gonna rub off, ‘cause they’ve seen me pick things back up for myself. And I think they realize in due time it’s gotta change for us. It’s just gotta.”

This is the way Gary Carter wants life to be, of course: his example showing the way to a simple and logical reality. No muss, no fuss. Such is why he took it on himself to get a bunch of Mets together in Chicago and went to the movies, Cocoon one night, Perfect the next. Togetherness, in Carter’s mind, breeds common cause. But life doesn’t always fold into snug designs: the Mets lost the last two games to the Cubs in Chicago, then three straight to the Cards.

For the most part, however, being around the batting cage in the open stadium air and bright sunshine is springtime for Gary Carter. He bops Ray Knight lightly on the helmet with a bat and serenades fading slugger George Foster by bellowing “George-ee! Georgeee!” “It’s interesting with Gary,” says a Met as Carter cuts up. “I wondered if he’d be a pain in the ass, but it’s the opposite. I know I look for his stuff: the way he smiles right into your face after a win and waits to high-five each player. We didn’t do that here before. It’s just a reassuring kind of thing.”

Except, again, Carter can take all the right steps and still get bubble gum stuck to his shoe. At the moment, the Expos, the team Met people snickered about in rustling away Carter for pumpkin seeds, are ahead of them, and had beaten Carter five of six games. For Carter, it had to be a silent vexation: If things stayed this way, would it mean the Expos got the better of the deal? Would it mean Carter was in fact a jinx?

That Carter has thought about it is evident by his reflex response to my easy remark that the people traded for him have panned out. “One’s on the disabled list and another’s hitting .190,” he says, grinning broadly and neglecting the solid play of Hubie Brooks. “They’re playing good ball now, but that doesn’t mean they’re·gonna stay there.”

But Carter grows halting, a bit out of synch and caught unexpected—yet is most revealing—when I ask how he’d feel if the Expos did win. “Well, I’d say it was a combination of things—the injuries and other reasons. If they do, more power to ‘em. And maybe I was the reason in that case—but I’m not gonna say that was it, just that they were able to finally put it together.”

The truth is Carter would be mortified if that happened, and crushed if he never wins a pennant. Indeed, his impatience with notions of personal defeat may be his way of escaping a fear of failure.

Carter, in form, treats that hypothesis earnestly, but with definite evasiveness. “I don’t think any player can fear failure,” he says, “because you’re gonna take it onto the field. You can’t play with that, no way.”

I then ask if there’s anything missing in his life, something needed to feel complete, specifying I don’t mean something in baseball, like a World Series. “But that’s just it,” he says, “It’s only a World Series, to be honest with you, because all the other things in life have already come.”

And, who knows, maybe there is something to his design, after·all. Later, Carter has a 1-for-4 night, knocking in the last run of a 6-2 Met win with a single to centerfield. By the All-Star break, Carter was hitting. 271 and the Mets had won eight in a row. Still to come, however, was the mid-July recurrence off his right knee cartilage problems (which put him in another hitting slump and threatened his and the Mets’ season) and more Mets spasms of spectacular rises and falls.

Still on this day in early July, Carter is at the zenith of his career. Maybe he at last can put aside his suffering at Montreal. Yet early in the season, after a base hit against the Reds, he stood on first base next to Pete Rose—the idol who had insulted him—and Carter said, “Pete, how could a guy that plays like you say that thing about me being too much of a kid?” Carter asked the question good-naturedly but with an eagerness to know.

“No, no. You got it wrong,” Rose told him. “What I meant was that I wished I had 25 kids like you.” Carter didn’t quite believe that, but he felt wonderful that the old warhorse had turned a grudge into a belated tribute. Indeed, given Carter’s new Queens digs and neighbors in the locker room, it must sometimes seem that there never was a Montreal in his past. But only sometimes.