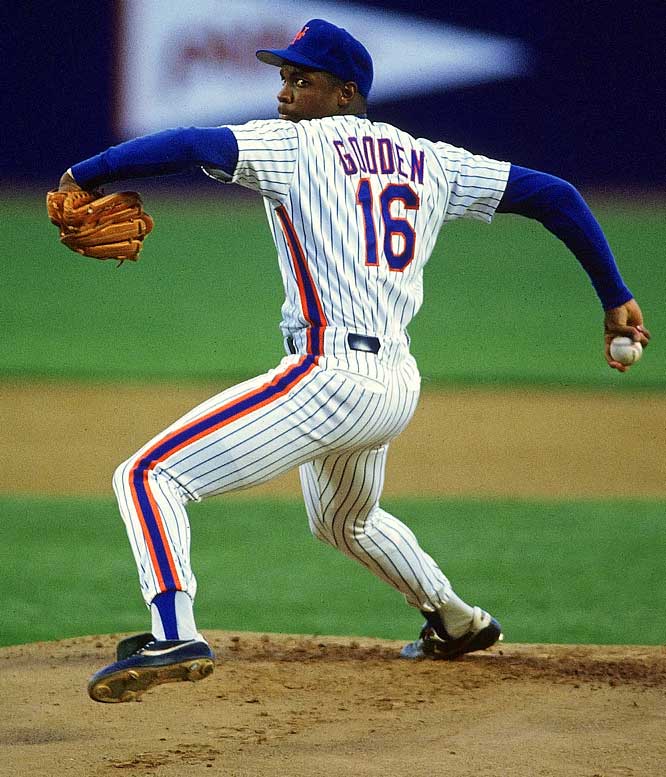

By the time I arrived at Shea Stadium in mid-June, a Dwight Gooden start had become a New York event. I had been watching Gooden baffle opponents on television over the first two months of the 1985 season. The first month he shut out the Philadelphia Phillies twice and the Cincinnati Reds. From May and early June he pitched into the seventh inning in all seven of his starts. He was four days younger than I was for goodness sakes. It was time to see this with my own eyes, in person.

Traffic was bumper-to-bumper (like I said, a Gooden start had become an event). More than 51,000 packed Shea Stadium on this Wednesday night. The mild evening was near perfect for baseball as Bob Murphy, the soundtrack of summer, piped through the car stereo. “Not a cloud in the sky. It’s a perfect night for baseball,” his voice echoed from car-to-car as the Mets prepared to face then National League East rival Chicago Cubs. The first official day of summer was still two days away but you could already feel it in the warm air as we listened to the first inning on the radio, smell it in the breezeway and up the ramp to our seats in the upper deck behind home plate and throughout a stadium bracing for greatness.

The Mets manufactured a fourth-inning run and that was it. My stained scorebook says Gooden struck out Thad Bosley to end the game. A complete game, 1-0, six-hit shutout; Gooden was as good as advertised. I don’t know, maybe it was the fact that it was the first time I’d ever been to Shea Stadium when it was close to sold out (on a Wednesday night!), maybe it was the fact that the Mets were actually in contention, but seeing Gooden pitch – live – in 1985 was like no other experience I’d ever had at a major league ballpark.

He would go on to win 14 consecutive decisions, including No. 20 against the San Diego Padres (which I still have the WOR feed recorded on VHS) and 18 of his final 19 decisions of the season, including two shutouts and a complete game over the final three weeks of the season. Gooden finished 1985 with this line: 35 starts, 24-4, 1.53 ERA, 276 IP, 268 K, 16 complete games, 8 shutouts.

I have never personally experienced a pitcher more dominant than Dwight Gooden was in 1985. That’s not to suggest a pitcher, even a New York Mets pitcher, hasn’t flirted with the same level of excellence.

I have never personally experienced a pitcher more dominant than Dwight Gooden was in 1985. That’s not to suggest a pitcher, even a New York Mets pitcher, hasn’t flirted with the same level of excellence.

Case in point: George Thomas Seaver, “The Franchise,” 1971. You could argue he had better years statistically, but it would be hard to challenge his performance that season. Seaver finished 20-10 in 36 starts with a 1.76 ERA. He pitched 286 innings, recording 289 strikeouts, including 21 complete games and four shutouts.

Take a closer look at the games Seaver lost; they are deceiving. In the 10 games he was tagged with a loss it was by a total of 16 runs combined – 3-1, 5-4, 3-2, 2-0, 6-4, 5-3, 2-1, 3-2, 1-0 and 3-0. The Mets scored a total of 17 runs in Seaver’s 10 losses (which included a loss in a relief appearance in the second game of a doubleheader against the Cincinnati Reds). In half of the games the Mets scored one or no runs, including three shutout losses.

The win column is equally deceiving. Seaver pitched two complete game shutouts (technically) and didn’t get a decision in either game. He pitched nine shutout innings against the Reds and left the game with a no-decision. On August 11 Seaver pitched one of the finest games of his career: 10 IP, 0 R, 3 H, 14 K, 2 BB and a no-decision. The Mets eventually lost the game 1-0 in 12 innings on a throwing error by Jerry Grote.

Seaver finished second to Ferguson Jenkins in the 1971 Cy Young Award vote. Why? I am not sure. Seaver was better – much better – on paper. Jenkins won 24 of his 39 starts and pitched 325 innings that season, but he also had an ERA of 2.77, one full run/game higher than Seaver. He also gave up 304 hits and allowed almost twice as many runs as Seaver (100, Jenkins/56 Seaver). Still, Jenkins received 97 votes to Seaver’s 61. But I digress.

This scenario began germinating in my head last week after a co-worker asked me this question: If the Mets were playing in Game 7 of the World Series and you could pick any pitcher in team history to start the game (assuming they were at the peak of their pitching career), who would you pick? Tom Seaver? Dwight Gooden? Matt Harvey?

This scenario began germinating in my head last week after a co-worker asked me this question: If the Mets were playing in Game 7 of the World Series and you could pick any pitcher in team history to start the game (assuming they were at the peak of their pitching career), who would you pick? Tom Seaver? Dwight Gooden? Matt Harvey?

Did you say Matt Harvey? I nearly spit out my $5 Starbucks Caramel Macchiato coffee.

What’s so funny?

The idea that anyone would put Harvey in the same conversation, the same sentence, the same question with Gooden and Seaver – that’s what’s so funny.

Before I write one more word let me be perfectly clear: one day, not too far from now, barring injury, I believe, Matt Harvey will have earned the right to share in this hypothetical discussion, but not right now.

Harvey has the talent, the “makeup” and he is quickly earning the respect of hitters from all corners of the Major League Baseball map. But, my goodness, Matt Harvey has won 10 major league games. To put that in context he only needs to record 301 more to match Seaver and a mere 184 more wins to equal Gooden. Seaver won four Cy Young Awards and Gooden one. Let’s get Harvey through his first All-Star Game, in his first full season, in the majors.

Success leads to fame and fame leads to expectation, and when it happens this quickly (in this case, three months) it’s scary, and to some degree unfair, to heap that much pressure on a young man (in New York, no less). Can Harvey do it — what his predecessors, Seaver and Gooden, did in New York? There is every indication by his performance and maturity that he will, but it will require time — seasons — before we will be able to drop Harvey’s name in the same conversation with Seaver and Gooden.

(Photo Credits: USA Today, Sports Illustrated)