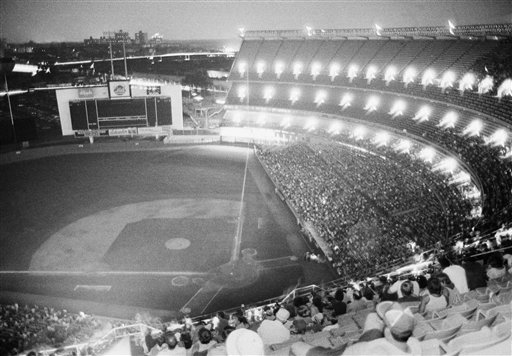

NYC Blackout Shuts Out Shea In 1977

It had been a sweltering hot summer in NY, so hot that my dad and I had taken to sitting out in the backyard to listen to the games. It was July 13, 1977, and the Mets were playing the Cubs. They were losing 2-1 in the bottom of the sixth in spite of an 11-strikeout effort by Jerry Koosman. We were eating watermelon and cheese. I remember spitting watermelon seeds out towards the tomato plants occasionally bouncing a seed off the big red tomatoes hanging from the vines.

Jerry Koosman, who had always been good, had never been Tom Seaver great. If we went to a game and Koosman was pitching it was like getting almost what you wanted for Christmas, like getting a pair of Pro-Keds instead of the Converse hightops you had your eye on … I was 12, what did I know? I’d been spoiled by one of the greatest ever to pitch off a mound and I was still reeling from having lost my all-time favorite NY Met. With Seaver gone, you’d think I would have grown to appreciate Koosman’s ability, but it was just the opposite. I grew to resent Koosman even more because he wasn’t Tom Seaver. Koosman became something like a bad imitation, an imitation that offered no consolation when the real thing ended up being taken away forever.

So we listened to the game and swatted mosquitoes and ate watermelon and sharp Greek cheeses. My mom and my sister weren’t home because my sister was in class over at Queens College and my mom had taken the car to go pick her up. Normally my sister would take the bus, but lately my mom had become so worried about this .44 caliber killer the tabloids had tabbed “Son of Sam,” that she’d taken to driving her out and picking her up every night.

My sister also happened to be a long-haired brunette which apparently was a favorite target of this particular psycho. Anyway, we’re listening with Lenny Randle at the plate and Ray Burris pitching and suddenly there’s a roar in the crowd and Lindsey Nelson starts going on about the lights going out in the stadium and just as I was explaining to my Dad that the lights had gone out (he had a hard time with any English vocabulary that wasn’t specific to his remarkably complete baseball lexicon – he even knew what a balk was) the radio went dead. It didn’t hit us at first because there weren’t any lights in the backyard, so we were just kind of staring at the radio wondering what happened. Then we heard the yelling and screaming from all around us and realized the lights had gone out, all the lights, everywhere.

It was becoming a long night as we sat in the hot kitchen lit only with a few old Easter candles while my dad paced back and forth chain-smoking. We were waiting for my mom and sister to get home. We had no idea where they were or how they’d get back in the dark. Eventually they did manage to get home without getting shot or looted, well past 11:00 PM. We were just happy to be together and safe.

It was becoming a long night as we sat in the hot kitchen lit only with a few old Easter candles while my dad paced back and forth chain-smoking. We were waiting for my mom and sister to get home. We had no idea where they were or how they’d get back in the dark. Eventually they did manage to get home without getting shot or looted, well past 11:00 PM. We were just happy to be together and safe.

My sister later explained that Mom had pretty much driven the entire way never exceeding 15 miles per hour with the windows up and never coming to a full stop. We ended up laughing a little as my parents fretted about spoiled cheese and melted butter at the store (my family owned a small deli on Roosevelt Ave.), and after a while we didn’t even mind the dark so much as we drifted off to bed. The noise of the increasingly more distant and sporadic yelling continued to waft through our open windows throughout the night with my dad keeping a quiet vigil at the front of the house, guarding from whatever chaos might happen by.

My friend Andy from across the street who was three years my elder was at the game that night with his cousins. He told me all about it the following day the same way he’d retell rated R movies scene for scene, word for word. I’ll never forget listening to him recite Jaws in all it’s gory and suspenseful detail, I swear it took longer for him to retell the movie than the movie itself. It took him a week to finish the Exorcist.

Anyway he explained how they didn’t realize it was a city-wide blackout until they were filing out and heard from people who’d been in the upper decks that the entire grid was black. He described the strange scene on the field as the players drove their cars onto the outfield grass with their headlights on and mimed infield practice to entertain the fans while the organist played Christmas music. Emergency generators lit up parts of the the stands but many of the halls and corridors were pitch black. Eventually they tired of waiting and slowly made their way out. They ended up walking the entire way back to 98th street, Corona.

Thinking back to that summer I can’t imagine a more fitting metaphor to losing the Franchise, Tom Seaver, than being left dumbfounded in the dark with a dead radio in the middle of a game. They’d turned the lights out on us and herded us into the pitch-black unknown. I’ll never forget the front page of the Daily News, “Seaver to Reds; Kingman to S.D.” We couldn’t make any sense of it. I read the paper to my dad and we concluded it was all about money, but I was way too young to understand anything about free agency or renegotiating contracts or personal pride.

Thinking back to that summer I can’t imagine a more fitting metaphor to losing the Franchise, Tom Seaver, than being left dumbfounded in the dark with a dead radio in the middle of a game. They’d turned the lights out on us and herded us into the pitch-black unknown. I’ll never forget the front page of the Daily News, “Seaver to Reds; Kingman to S.D.” We couldn’t make any sense of it. I read the paper to my dad and we concluded it was all about money, but I was way too young to understand anything about free agency or renegotiating contracts or personal pride.

What precipitated the split was the new Collective Bargaining Agreement that was signed on July 12, 1976. It was the beginning of free agency. Only four months earlier, the Mets had signed Seaver to a three-year, $675,000 contract, and he was, at that time, baseball’s highest paid pitcher.

Later that winter as the first batch of free agents cashed in with players signing million dollar contracts (even Nolan Ryan ended up making more than Seaver as Gene Autry offered him a 300,000 dollar base salary in lieu of Nolan’s impending free agency), Seaver wanted to renegotiate. But the bitter pill for fans came after the realization that there was actually a renegotiated contract in place that would have kept Seaver in Queens when a story by Dick Young appeared in the Daily News describing how Nancy Seaver was jealous of the Ryans.

That was it for Tom Terrific, he wanted out and he got his way. None of the participants, not Seaver, not Grant, not Young, not even Nancy, ever stopped to consider that their actions would leave some kid out in Queens very much … in the dark … eating cheese, and spitting watermelon seeds.