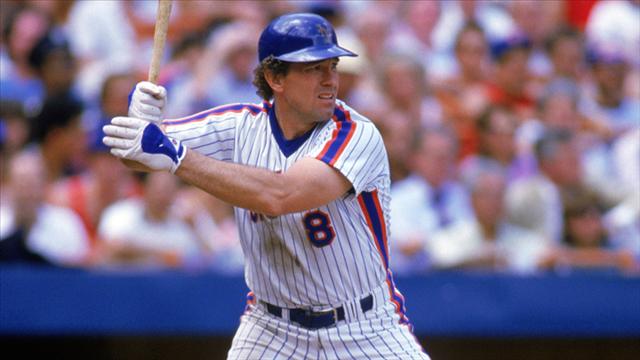

After Gary Carter got a hit with two outs in the bottom of the 10th in Game Six, he turned to 1B coach Bill Robinson and said, “There’s no way I was making the last ******* out.” Moments later, pinch hitter Kevin Mitchell, void of his cup, got a base hit. He turned to 1B coach Bill Robinson and also said, “There’s no way I was making the last ******* out.”

When you look at the Mets today, do you see that same determination?

There’s a difference between playing to win and playing not to lose. When I watch the Mets, I see the latter. I see a team that’s not loose, that’s timid, almost waiting for something to go wrong and have a loss snatched from the jaws of victory.

I look at the Mets and, even this early into the season, it appears they are going through the motions. Willie Stargell once said, “Baseball is fun. That’s why the umpire says ‘Play Ball,’ not ‘Work Ball.” But to me it doesn’t seem like the Mets are having fun. They play hoping for the best but expecting the worst.

Last Friday night, the Mets arrived in Anaheim after a cross-country flight from Atlanta. But you’d think they were the first team to ever do this. They seemed lethargic, a far off distant look in their eyes. If this was the dog days of August I’d understand. But to see—in my view—a team this weary and this sluggish on their first road trip of the season made me wonder.

In the top of the 3rd, Travis d’Arnaud hit a solo HR to tie the game at 2-2. It was only the second homer of his career. Upon returning to the dugout, d’Arnaud smiled briefly, got a couple of proper pats on the butt from teammates and promptly sat on the bench putting on his catching gear. Very formal, very businesslike.

Three innings later, the opposite happened. J.B. Shuck, just called up to replace injured Josh Hamilton, hit a HR in the bottom of the 6th to knot the game at 4. It was the only the third of his career. Several of his teammates stepped onto the field, giving him high-fives after he rounded the bases, hugging him as he walked through the dugout. By the Angels’ reaction, you’d think it was a post-season game in October, not a Friday night in early April.

The stark difference was…amazing. The Angels were ecstatic, exuberant, nine-year-olds in Little League. The Mets were blasé, nonchalant, and almost indifferent.

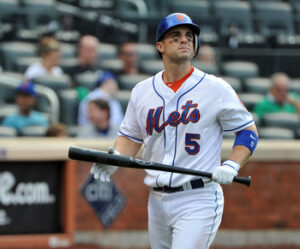

In the 1970’s our hitting was definitely anemic. But out excellent pitching and stellar defense always kept us in the game. We had a legitimate chance to win. At the end of the 20th century, we had good enough pitching and enough big hitters that a win, no matter the score, seemed within our grasp. From 2005-2008, with a lineup consisting of David Wright and Jose Reyes—both coming into their prime–the power of Carlos Delgado and the 5 tools of Carlos Beltran, no deficit seemed insurmountable.

And then, there was ’86. If the Mets jumped out in front, it felt as if ‘that’s the way it’s supposed to be.’ Business as usual. And if we fell behind, our confidence never wavered. It wasn’t a matter of IF we’d win but HOW. And we did win. 2 of every 3 all year. But now it’s just the opposite. It feels like when the Mets take a lead, we don’t count on the win. Instead we ‘hope the bullpen can hold it.’ And if we fall behind, well, that’s when it feels like business as usual.

Why is this? Where does this culture stem from? When and how did mediocrity become acceptable and losses expected? Does it start in the executive office with ownership and the GM? Is it the fault of the manager and coaching staff? Perhaps, the players themselves?

When you look back at the good times there is one underlying consistency. We created a culture of winning.

On Opening Day 1969, Tom Seaver was a 24 year-old kid, Jerry Koosman was 26, Gary Gentry didn’t even look old enough to shave and Wayne Garret looked like he arrived at Shea via his tricycle. They were inexperienced kids but yet they won. How? The reason is they were surrounded by people who were winners. Manager Gil Hodges and coach Yogi Berra had played in 114 World Series games combined!

In June, management acquired Donn Clendenon, the player who Buddy Harrelson stated, “…gave us credibility.” Clendenon spent the bulk of his career in Pittsburgh alongside the likes of Stargell and Roberto Clemente, players who knew how to win.

When the Mets returned to the Series four years later, much of the team were holdovers from ’69. They were already champions.

By 1986, we had young stars like Gooden, Strawberry, and Dykstra. But we also had Gary Carter who, at this late stage in his career, would’ve done anything to get a ring. Keith Hernandez already had a ring as well as an MVP on his mantel. And at the helm was Davey Johnson, a player who spent the bulk of his career playing under Earl Weaver, one of the games’ winningest managers. Davey had two rings. He knew about winning.

The 99/00 club didn’t have “winners” but we had a roster loaded with guys who had that fire in the belly: Piazza, Ventura, Franco, Leiter, Payton. Even over-achiever Benny Agbayani.

Around 2006, we had the perfect blend of young talent and veterans who knew the game. Delgado was running out of time to become a champion, Beltran was determined to quiet the critics, Pedro Martinez was a big game pitcher, El Duque was a post-season stud, Paul Lo Duca played with the passion of Jerry Grote. And our skipper, Willie Randolph, had won 5 pennants and 4 World Series.

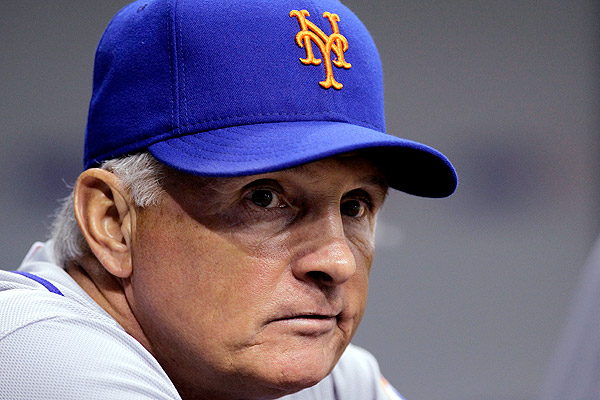

Which one doesn’t fit in with this group: Hodges, Berra, Johnson, Valentine, Randolph, Collins.

The 2014 Mets are centered around David Wright. Like Seaver before, he is the face of this team. He already holds many team records and by the time he hangs up his cleats, he will be at the top of every offensive category in our history. We all love him, no doubt about that. It’s as if we get through the other 8 guys just to get back to Wright, who seems like he’s the only one who can give us a chance. And although we all love him, he can’t be called a winner yet.

That’s not a knock on David. Cooperstown is filled with legends who never won a ring. No one should diminish the accomplishments of Ernie Banks, Juan Marichal, Tony Gwynn, Nap Lajoie, Ted Williams and countless others. And while David puts up great numbers year after year, he can’t be lumped together with winners like a Pete Rose, Reggie Jackson, Keith Hernandez, Tom Seaver, Derek Jeter and Dustin Pedroia.

The 2014 Mets do have Curtis Granderson, a player with extensive post-season experience. But can he be labeled a ‘winner?’ In 36 post-season games he’s compiled a paltry .229 BA. His one World Series appearance, 2006 with Detroit, his team lost in five. Granderson went 2-for-21, an .095 BA.

When I look at the Mets today, I see a lot of things. I see management that operates a big market club with a small market mentality. I see a GM whose hands are financially tied, searching the bottom of the barrel, hoping for one more good year from players well beyond their prime. I see a manager and a coaching staff who has never won. I see a third baseman who’s the only real player we have on our team, a role model for kids, but not a champion. I see the future of our team, Matt Harvey, a 25 year-old who has already undergone Tommy John surgery. I also see potential. Young pitchers with a lot of upside who are still unproven.

I see a lot of different things. Regrettably, though, I don’t see any winners.