Brad Penner-USA TODAY Sports

The 2021 campaign did not go according to plan for Carlos Carrasco and the Mets. Carrasco was a key piece of an off-season trade in which the Mets also acquired Francisco Lindor. However, due to injuries, Carrasco’s Mets debut did not occur until July 30, and he never looked quite right on the mound. The 2022 season, though, has been a completely different story for Cookie.

Carrasco’s traditional statistics look good so far in 2022, including 10 wins (tied for third in the National League) and 100 strikeouts in 99 innings. However, when considering a slightly more advanced metric— Fielding Independent Pitching (FIP)— Cookie’s bounce back is even more impressive.

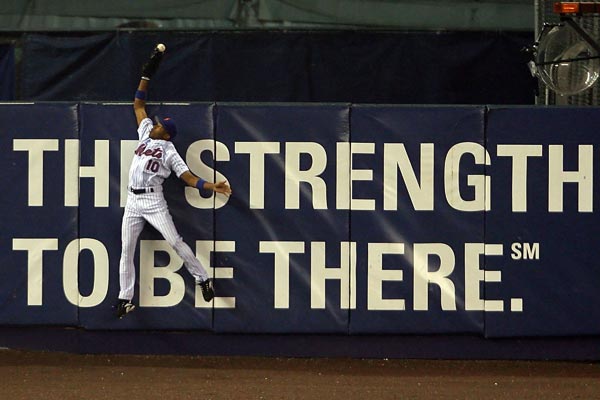

Unless it is hit towards them, a pitcher has no control over what happens once a batted ball is put into play. Instead, he relies on the skill, positioning, and acumen of the eight fielders behind him, and even his own, as a pitcher is counted as just another fielder when computing stats like earned runs. Therefore, a batted ball entering the field of play introduces a considerable amount of luck that can influence a pitcher’s statistics. Commonly used metrics such as ERA, however, do not account for the variability of fielding. Indeed, for the purposes of that measure, all outs recorded by fielders are equal, whether it’s a routine fly ball or one of the greatest catches of all time.

ERA counts Endy Chavez‘s legendary catch as equal to a routine pop-up.

Further complicating matters, a pitcher’s ERA can also be influenced by sequencing, another factor not truly indicative of their skill. For example, we can think about two pitchers, A and B, both of whom allow six hits over six innings pitched, all of them singles, and no other baserunners. Pitcher A scatters those hits equally over the six innings, one per inning, and allows zero runs. Pitcher B, however, allows three consecutive singles in the second inning, and again in the fourth innings, with a run-scoring in both instances. Therefore, while Pitchers A and B were equally effective in preventing baserunners, Pitcher A winds up with a perfect 0.00 ERA for the start, while Pitcher B earns an ERA of 3.00. FIP is therefore a handy tool because it only considers outcomes that a pitcher has complete control over, namely strikeouts, unintentional walks, hit-by-pitches, and home runs. It simply ignores balls hit into play, since those results are not believed to be as accurate a reflection of a pitcher’s performance.

How is FIP calculated? According to the MLB Glossary, the formula is ((HR x 13) + (3 x (BB + HBP)) – (2 x K)) / IP + FIP constant. The ‘FIP constant’ at the end of the formula is simply a number used to put FIP on the same scale as ERA and adjust the league average FIP to match the league average ERA. This allows us to look at a FIP value and interpret it the same way as an identical ERA value. For example, a FIP below 3.00 would generally be quite strong.

Since, like ERA, a higher FIP is bad, and a lower one is good, we can now understand more clearly how the formula works. As homers are quite damaging to a pitcher, FIP punishes them quite severely for allowing one, to the tune of 13 for each. Walks and hit-by-pitches are also bad for pitchers, but not nearly as much as a home run, so each one only counts as 3 in the FIP calculation. Meanwhile, strikeouts are a huge asset for pitchers, often representing a best-case scenario, since they prevent bad things from happening, not only hits, but also other events that can harm a pitcher, such as errors, misplays, and sacrifice flies. This makes strikeouts a crucial component of the FIP formula, and they are assigned a negative number, given their many benefits to a pitcher.

Jumping back to the topic of Carlos Carrasco’s rebound, it turns out that solely considering ERA actually understates his improvements in 2022. Cookie’s 4.27 ERA, inflated recently by a few tough starts versus Houston, may seem a bit underwhelming. His FIP, however, is a solid 3.51. Why is there such a large gap between ERA and FIP? Well, this tells us that Cookie has overall pitched quite effectively, and perhaps received some bad luck. In terms of what he can control, Carrasco ranks among roughly the top 25% of pitchers in walks issued, is allowing fewer homers than the league average and is striking out more batters than average. Thus, Carrasco has likely been victimized by some poor luck this season.

Indeed, a few big innings have inflated his ERA, such as a six-run inning for the Phillies, in which five of the runs were charged to Cookie, the final two on a Garrett Stubbs three-run homer allowed by Chasen Shreve. Indeed, had some of the batted balls that inning been turned into outs, or had Shreve not allowed the inherited baserunners to score, Carrasco’s season ERA would be lower. As a result of all this, we can conclude that if he continues to throw the ball this well and stay healthy, Cookie should continue to pitch like an upper-end starter for the Mets, and his ERA should decline.

Like all statistics, FIP has its limitations. By ignoring batted balls, we are removing some key metrics that can predict a pitcher’s success, namely the quality of contact he allows. If a pitcher consistently gives up hard hit balls, they are more likely to fall as hits, which should result in more runs allowed and a poorer outcome for his team. It can be challenging, however, to distill batted ball statistics down into a single number, as several metrics, including average exit velocity, expected batting average, and barrel percentage, all contribute. So, if you are trying to quickly assess a pitcher’s effectiveness, FIP is an excellent tool to use. Plus, for Mets fans, here is a handy way to end a debate: The active leader in career FIP, by a wide margin? One Jacob Anthony deGrom.